A Proposed AI Strategy for 2024: Agency, Not Agents

Or, what inquiry-based learning can teach us about how to approach AI.

Earlier this month, before they may or may not have fired their CEO, OpenAI announced a new feature of ChatGPT: “GPTs,” or customizable bots that can perform specific functions we define. This is a step towards a world filled with AI “agents,” where generative AI does not just create what we prompt it to, but acts on our prompts. AI agents will eventually be able to work autonomously, making calls, designing and launching software, and other tasks we associate with office or knowledge work. As he always does, Ethan Mollick has a detailed and thoughtful review of GPTs for those who want to dive more deeply into how they work.

Because I pay for access to ChatGPT-4, I’ve been able to spend some time creating GPTs. Like any new technology, current performance isn’t living up to potential, but there are a few features we should pay attention to:

Ease: You create a GPT through interacting with a “GPT Builder,” which is just a chatbot. The Builder asks you questions about the purpose, persona, and rules for your GPT, and it updates the GPT accordingly. GPTs are created in a split screen: you interact with the Builder on the left and with your GPT on the right. You can input initial instructions, test your GPT, then go back and refine it in the Builder. You can further edit instructions for your GPT by moving from “Create” mode to “Configure” mode. For me, the GPT Builder is a more intuitive and more robust version of Poe’s Create a Bot tool (which is still a great free option if you want to experiment with customizable bots).

Customization: Not only can you train a GPT to perform a specific task, you can upload files and ask the GPT to work with them as a knowledge base. I’ve trained a GPT to locate, summarize, and reference elements of the Biden administration’s recent executive order on AI regulation. I’ve trained a GPT to use handbooks, mission and values statements, and other foundational documents from a school to draft AI policy statements aligned to a that school’s specific identity. It’s easy to imagine a teacher (or a student) training a GPT on course materials, class communications, and other resources to create an on-demand teacher avatar.

Shareability: As of this writing, you can only share GPTs with other ChatGPT-4 subscribers. I don’t share mine because of reports that shared GPTs can be hacked. Still, we should be thinking about the implications. Shareability is what makes GPTs very similar to apps, except no coding is required. Everyone with access to ChatGPT-4 can now build digital tools that perform specific tasks (like a teacher avatar) and then make them widely available.

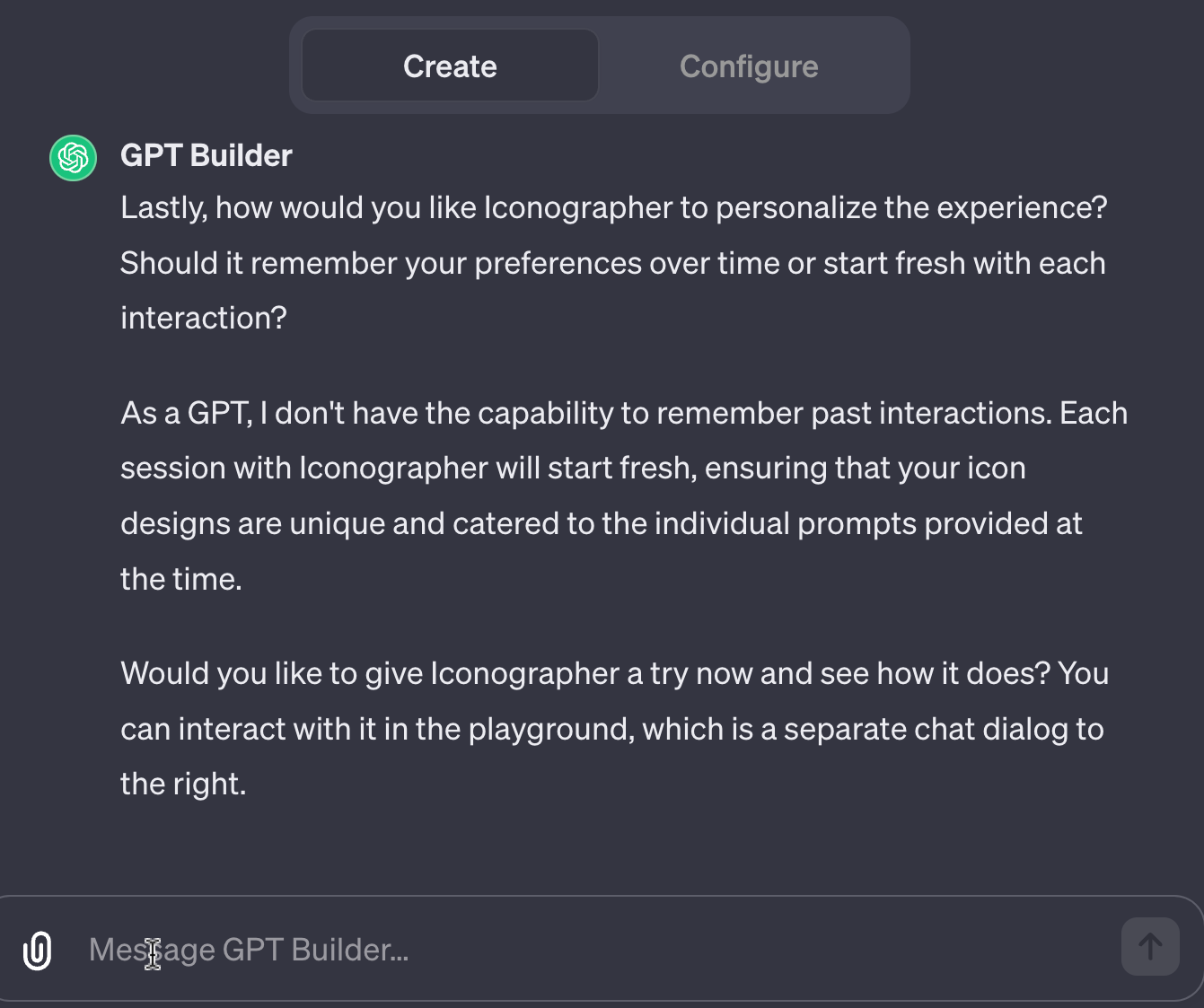

I also ran into some problems with GPTs. Here’s an image of the Builder asking me follow-up questions about an icon generator GPT I was trying to make and then… answering those questions itself.

At one point it got confused as to which side was the Builder and which side was the GPT. Here’s me trying to find the Builder and being denied.

My GPTs also replicated many of the flaws we would find in any AI chatbot: they hallucinated (presenting false information as if true), they often failed to limit their responses to the documents I uploaded as the knowledge base, and they sometimes required repeated prompting to perform certain functions correctly. I had to use my own prior knowledge or Google to vet its responses, and I did a lot of re-prompting and re-training.

Eventually, I found myself thinking, “I’ve been here before.”

The AI Inquiry Cycle

I share this image with schools when I talk about approaching AI:

Inquiry-based learning is a cyclical process that invites students to ask open-ended questions about topics that matter to them and to the world beyond school. Exploration of these questions through research and experimentation develops skills that are critical components of agency: self-awareness, goal-setting, and resilience, among others. (Resources on inquiry-based learning abound, but I like this old but excellent overview from the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine).

The cyclical element is essential: seeking answers to questions should spark new and more complex questions. Each cycle equips us to take on more complexity and rigor in our thinking and to be motivated to embrace that challenge. As I stumbled my way through learning about GPTs, using all the AI skills I already had (and questioning whether I really had them), I realized how important this cyclical approach has been to how I learn about AI.

When I think about AI strategy for schools, I think about agency. What does it look like to make decisions, allocate resources, and frame communications in a way that creates empowered AI users? How can schools support open exploration of AI in a way that builds the skills and knowledge educators and students need to leverage AI for their own goals, not be passive observers of its rise?

I think an inquiry-based approach can help.

Make Sense of AI: This is about building literacy. Schools need to provide educators and students with accurate information and hands-on experiences related to AI so they can make informed decisions about if and how to use it. As I’ve written about before, hands-on practice very quickly reveals all the ways AI can be both powerful and mediocre, both helpful and unreliable. It builds basic AI skills like prompting and dialogue and critical review of outputs. It also reveals possibilities: making sense of AI allows each of us to start asking and exploring questions about how it applies to our specific contexts and goals.

Talk About AI: I advocate for making sense of AI with colleagues and with students because it’s a way for us to talk about AI. When I facilitate AI workshops, everyone is on their devices trying prompts, but they are also showing AI outputs to each other and comparing what they are seeing and what they are thinking. I recently spent a few weeks speaking at schools, and I was genuinely surprised by how much teachers were talking to each other about AI, how much students were talking to each other about AI, and how little they were talking to each other about AI. If we are going to support students in using AI responsibly, we have to start by asking them about their experience with it, learning from their work, and creating shared AI experiences we can have with them.

Co-Construct Guidelines: I’m doing more and more advising of leadership teams on position, strategy, and policy for AI. This is important work, but publishing institutional policies is a beginning, not an ending. Policies are tested and refined in the day-to-day interactions of teachers and students. Specifics matter: even with a robust school policy on AI, how we use AI in 11th grade chemistry class might look different from how we use it in 8th grade history class. The use cases that are valuable and appropriate in English class might not apply to world language classes. Talking about AI invites colleagues and students to curate and create these use cases together, increasing the chances that guidelines are relevant and are followed.

Explore Responsibly and Responsively: I am almost daily hearing about an innovative and productive use of AI by a teacher, administrator, or student. Schools should be using their guidelines to encourage exploration, to make the guidelines come alive by applying them to the actual day-to-day work of learning. Open, active exploration of AI is how we build the skills we need to understand and adjust to the new capabilities that are inevitably coming. We become prepared for and open to uncertainties and ambiguities. We are empowered to ask new and harder questions about how to use AI.

Education’s first trip through the AI inquiry cycle began with the debut of ChatGPT a year ago, when making sense of it involved being in awe of it (it can write essays and sonnets and lesson plans and college recommendations!) and being terrified of it (it hallucinates and might be sentient and is even creepy at times!). Talking about it involved mostly talking about cheating. Guidelines were mostly about bans or restrictions (and were not co-constructed), which made exploration not just difficult, but secretive. Students and teachers associated using AI with bad behavior, and so were less likely to explore and even less likely to share.

A Second Cycle

Now, I see schools entering a second cycle that is more open, taking an inclusive approach to this discussion that I hope leads to active learning, transparent communication, thoughtful and specific guidelines, and an increased sense of agency developed through intentional and ongoing exploration.

The goal for the major generative AI platforms and their owners is for AI to be so seamlessly integrated into our lives that we are barely aware of it, the way we are barely aware of being online or barely aware of the role smartphones play in our thinking and actions. Be ready for a time when we stop seeing, hearing, or using the term “AI” at all, even as we use the technology more.

Now, when these tools are imperfect, when they require us to use our own knowledge to verify and improve their outputs, when we have to think critically about how these tools are designed and trained, when even the companies who make them are uncertain about how fast or how much they want to develop AI, now is the time for us to take an inquiry-based, agency-building approach to AI for ourselves and for students.

Let’s dedicate our AI strategy in 2024 to agency, not agents. GPTs are a new, not-yet-impressive innovation that raise new questions about AI’s role in education. We can make sense of their new features. We can talk about the new use cases they present. We can revise our guidelines accordingly. And, we can keep exploring.

Links!

If you click on one link in this post, click on the AI Pedagogy Project by the metaLAB (at) Harvard. It’s a beautiful collection of high-quality AI assignments designed by educators.

John Warner (an excellent resource on the teaching of writing) tries to make a GPT avatar of himself and reflects on the results.

A profile of Mira Murati of OpenAI. If nothing else, the tumult at OpenAI reminds us that it’s helpful to learn about how leaders of these tech companies think about their work and their products.

An excerpt from the new book by Mike Caufield and Sam Wineburg, two of my favorite thinkers and writers about information literacy. Their work has never been more important.

Denise Pope and Victor Lee of Stanford University share preliminary data on AI’s impact on student cheating. Spoiler: AI hasn’t significantly changed the amount students cheat or the reasons why they cheat.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll share it with others. It’s free to subscribe to Learning on Purpose. If you have feedback or just want to connect, you can always reach me at eric@erichudson.co.