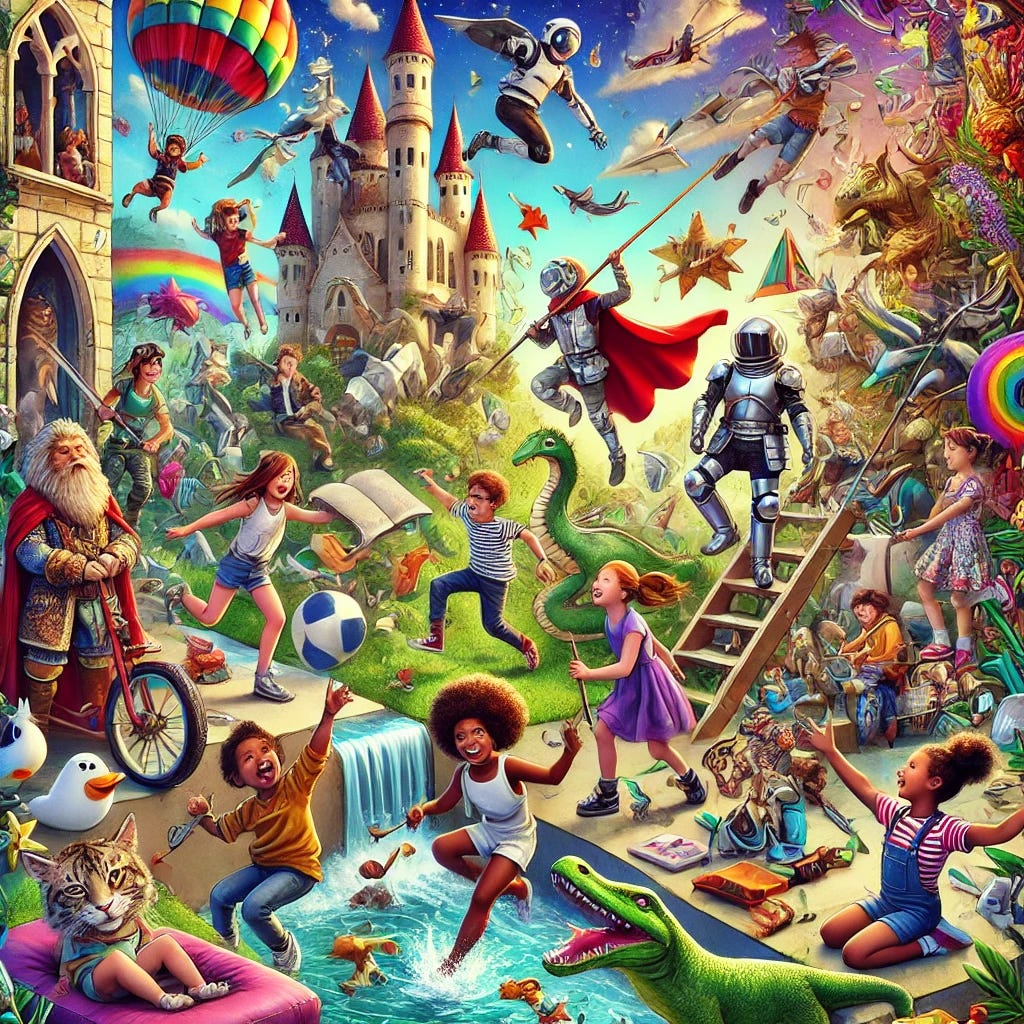

AI Skills that Matter, Part 3: Playfulness

What if we explored a serious topic by taking it less seriously?

This is part three in a four-part series about skills that both meet this AI moment and will outlast it. Part one is about extending the mind. Part two is about lateral reading. Part four is about ethical decision-making.

I am often asked, “What are the best uses of AI that you’re seeing?” My standard response is to rattle off a series of examples I’ve seen in my travels, but I’ve been trying to get clear about what these educators and students are doing with generative AI that inspires me. What is it about their approach that we can learn from?

The common ingredient is playfulness.

As I have in the other posts in this series, I’m going to lean on the work of a particular researcher. Peter Gray is a psychology professor at Boston College, and he writes the Substack “Play Makes Us Human,” which led me to his inspiring 2013 book, Free to Learn. I started thinking about Gray’s work in the context of generative AI for two reasons.

First, play builds essential skills. Children who play learn how to use and control their bodies, how to speak, how to build things, how to create and follow rules, how to imagine, and how to interact with others. The free-form, intrinsically motivated nature of play creates the conditions for students to learn new skills and persevere through challenges. Play is deeply rooted in evolution; it’s a way young members of many different species learn and practice the skills they need to survive. Play works because, as Gray writes in Free to Learn, “the player is playing for fun; education is the by-product.”

Second, the conditions required for meaningful play are human-centered. In Free to Learn, Gray reviews several studies that show that when we add stakes to a task—the prospect of being evaluated, of being punished, or even of being rewarded—our performance declines. We are more creative and we learn more deeply when we do not have to think about how what we do will be judged. Importantly for educators, research shows this is especially true for novices

Lowering the stakes is a prerequisite for another condition of play: positive emotions. If you let a person play freely for a few minutes, or watch a funny video, or even give them a bag of candy before performing a task, they will do better on that task. Setting a “playful mood” leads us to view the task as creative and fun rather than as a test or a job. Importantly, a playful mood does more than make the task more enjoyable; it produces more creative thinking and deeper insights.

The cultures of generative AI at most schools I visit are high-stakes and built on negative emotions like anxiety, anger, fear, or suspicion. When use cases of AI are discussed openly, those cases are most often abuses or unethical applications of the tool, not interesting or productive uses. When AI use is allowed, it is usually under extremely restricted circumstances and under threat of punishment if those boundaries are violated (disciplinary consequences, a reduction in a grade, etc.). The dominant culture of AI at schools is why teachers lower their voices when they tell me about their own use of AI, or why students appear scandalized when a teacher brings up AI in class, or why most school policies are more about dictating what people cannot do with AI and less about what they can.

Concerns about generative AI are important, but none of the negative emotions associated with these concerns is conducive to teaching students or educators how to explore generative AI in a productive way. Gray’s work on playfulness offers us an alternative approach: creative exploration in a human-centered learning environment.

Play vs. Playful

Gray offers four essential elements of play:

Play is self-chosen and self-directed.

Play is intrinsically motivated; means are more valued than ends.

Play is guided by mental rules.

Play is always creative and usually imaginative.

“Pure play” requires that all four of these elements are present. As we get older and take on more responsibilities, however, we have less time and less need for pure play. Gray makes a helpful distinction between “pure play” and “being playful,” which means introducing elements of play into our daily lives in ways that help us approach our work in a way that facilitates more creativity, freedom, and self-expression.

Play is self-chosen and self-directed.

When it comes to playfulness at school, Gray asks educators to think about power and control. Play requires agency, the sense that a person has ownership over their actions. The more freedom we have to make choices in our lives—no matter how old we are—the better we perform. Most schools are designed to put power and control in the hands of adults, and so in designing a playful activity, it is the adults who must make the decision to cede some power and control to their students.

I appreciate the playfulness of design challenges like this Hong Kong competition for students to use AI to reimagine school villages, or Mike Yates’ workshop on using AI to design sneakers to tell stories about education. In the hands-on segments of my workshops on AI, I begin by asking educators, “What’s a problem you’ve been trying to solve in your work? What’s a new idea you’ve been mulling for a long time but haven’t quite figure out how to make real?” I encourage them to bring those personal interests to their play with AI.

I should emphasize: students are already doing this. This week I was in a room with a couple of dozen students. Every single one of them uses generative AI, both for schoolwork and for personal interests like coding and design and just messing around to see what it can do. We should ask students about their experience and of course help them think about important issues of safety and privacy, but we should also recognize the value of this self-directed play. Students are learning a lot about AI by using it in their own ways.

Play is intrinsically motivated; means are more valued than ends.

One of the most important distinctions between “play” and “work” is whether a person is motivated by the process or the product. I loved how Gray describes constructive play in Free to Learn: “The primary objective in such play is the creation of the object, not the having of the object…It is possible to ruin play by focusing attention too strongly on rewards and outcomes.”

For example, instead of the teacher building an AI tutor or other kind of bot for students to use, the teacher could challenge the students to use a free tool like Poe to create their own custom bot. It doesn’t matter what the function of the bot is: the challenge is to train it to be effective at its assigned job, even—especially!—if that job is silly. Anyone who has ever tried to build a reliable bot knows that this is one of the more creative and challenging ways to work with AI. I’ll add, I have done this same activity with educators, and I regularly see as much humor, nonsense, and surprise as I do serious discussion of AI.

Play is guided by mental rules.

Play is not unstructured. Join children in playing make-believe, and you learn the rules very quickly. Games are fun because of the rules, because the rules create a new, fantastical world that people agree to explore together. According to Gray, the rules in play are how we learn self-control: we ignore certain impulses because we enjoy the game and are curious to see where it goes next. Rules in play are also important to what Gray calls “the freedom to quit,” which gives the player the right to leave the game once the rules become intolerable. The idea that we are choosing to follow the rules is essential

A playful approach to generative AI in this category could be about changing established rules, introducing surprise and creativity. What if, inspired by Joel Heng Hartse’s assignment asking students to cheat, you asked students to try to use AI to break rules or challenge school policies? Would they see that generative AI is not particularly good at or useful for certain tasks? Would they raise important questions about what matters about academic integrity and ethical use of AI?

You could extend the above build-a-bot activity to make it a competition: who can build the best (or—playfully!—the worst) bot at a certain task? How would students set the rules of the competition? Along the same lines, you could do what these researchers did: instead of asking students to learn from an AI bot, they were asked to teach one, with positive impacts on motivation and self-regulation.

Play is always creative and usually imaginative.

As I mentioned earlier, part of setting the conditions for play is setting the right mood. What if you began a class exploration of generative AI by showing students (of the appropriate age!) this AI skit from “Saturday Night Live” rather than reviewing school policy or reading a serious news article? How would this change both the content and the tone of the conversation?

Framing exploration of generative AI in this way detaches the activity from purely academic, high-stakes work and invites students to view AI as a powerful, flawed, and potentially hilarious technology. I’ve met many teachers who used class time to ask students if they could get AI to make a mistake or write something weird. A scroll through the AI Pedagogy Project’s recommended assignments will surface any number of activities that lead with creativity and curiosity. I especially like Leon Furze’s world-building activity and Maria Dikcis’ AI exquisite corpse game.

The Triviality is the Point

Generative AI is a serious topic. Part of a serious approach to AI, however, is being creative with it, exploring it with curiosity in order to understand it, and learning how to make effective decisions about when and how to use it. Decades of research shows that playfulness allows us to exert our agency over an experience, to explore new ideas and environments without fear, and to practice essential skills we need to succeed in novel situations. Play allows us to do these things because it is free of worry and impervious to external goals or pressure. Play is effective because of its lightheartedness, not in spite of it. As Gray writes, “We must accept play’s triviality in order to realize its profundity.”

Upcoming Ways to Connect with Me

Speaking, Facilitation, and Consultation

If you want to learn more about my work with schools and nonprofits, take a look at my website and reach out for a conversation. I’d love to hear about what you’re working on.

In-Person Events

February 24. I’ll be at the National Business Officers Association (NBOA) Annual Meeting in New York City. I’m co-facilitating a session with David Boxer and Stacie Muñoz, “Crafting Equitable AI Guidelines for Your School.”

February 27-28. I’m facilitating a Signature Experience at the National Association of Independent Schools (NAIS) Annual Conference in Nashville, TN, USA. My program is called “Four Priorities for Human-Centered AI in Schools.” This is a smaller, two-day program for those who want to dive more deeply into AI as part of the larger conference.

June 5. I’m a keynote speaker at the Ventures Conference at Mount Vernon School in Atlanta, GA, USA.

June 6. I’ll be delivering a keynote and facilitating two workshops (one on AI, one on student-centered assessment) at the STLinSTL conference at MICDS in St. Louis, MO, USA.

Online Workshops

February 19. I’m part of a free webinar presented by AI for Education, where I’ll be in conversation with the team about my “Four Priorities for Human-Centered AI in Schools.”

February 20. After the first session sold out, California Teacher Development Collaborative (CATDC) and I are pleased to offer a second run of “AI and the Teaching of Writing.” Open to all educators, even if you don’t live or work in California.

Links!

Peter Gray is a former collaborator of Jonathan Haidt, and his critique of Haidt’s book The Anxious Generation is worth a read.

The emergence of the Chinese model DeepSeek is the latest AI bombshell. Claire Zau’s detailed summary is a very good explainer, and Karen Hao concisely explained on LinkedIn why DeepSeek’s capabilities question a lot of assumptions we have made about what is required to create powerful AI models.

I love how Ravit Dotan tests for chatbot bias and crafts anti-bias prompts.

Jon Ippolito did his own research to try to figure out what we actually know about the environmental impact of generative AI, specifically the data centers that power it.

English teacher Tim Donahue makes a passionate case for at-home writing in the age of AI. His experience aligns with what I see and hear at many schools: moving all writing into class doesn’t serve student learning, and students see it as a sign of mistrust.

Phillipa Hardman reviews recent studies on generative AI’s impact on student learning. Spoiler: if the bots are deployed without sound pedagogical methods, they aren’t helpful.

If you’re not yet tired of my musings on AI, you can read a wonderful conversation I had with Liza Garonzik of R.E.A.L. Discussion about AI’s impact on the pedagogy of classroom discussion, and you can listen to this interview on working with teachers on AI with Michael Shipma of the Alabama Independent Schools Association.

In my work with students, play and enhancing creativity is one of the core tenets of AI exploration! Thanks for articulating it so well.