How to be a "Human in the Loop"

Using AI should spark agency, not deaden it.

I’ve been searching for a more concrete and practical way to explain what human-centered use of AI looks like, and lately I’ve been learning about how to be a “human in the loop.”

I discovered the term in this 2019 article by Ge Wang, a music and computer science professor at Stanford. He advocates for a human-centered, values-driven approach to AI systems design that recognizes where and how we derive meaning from different tasks.

“We don’t just value the product of our work; we often value the process. For example, while we enjoy eating ready-made dishes, we also enjoy the act of cooking for its intrinsic experience — taking raw ingredients and shaping them into food... It’s clear there is something worth preserving in many of the things we do in life, which is why automation can’t be reduced to a simple binary between ‘manual’ and ‘automatic.’ Instead, it’s about searching for the right balance between aspects that we would find useful to automate, versus tasks in which it might remain meaningful for us to participate.”

This pre-ChatGPT insight reflects the most common concern I hear at schools in the post-ChatGPT era: that AI is threatening the value of learning processes (like writing) because it is so efficient at generating competent versions of learning products (like essays).

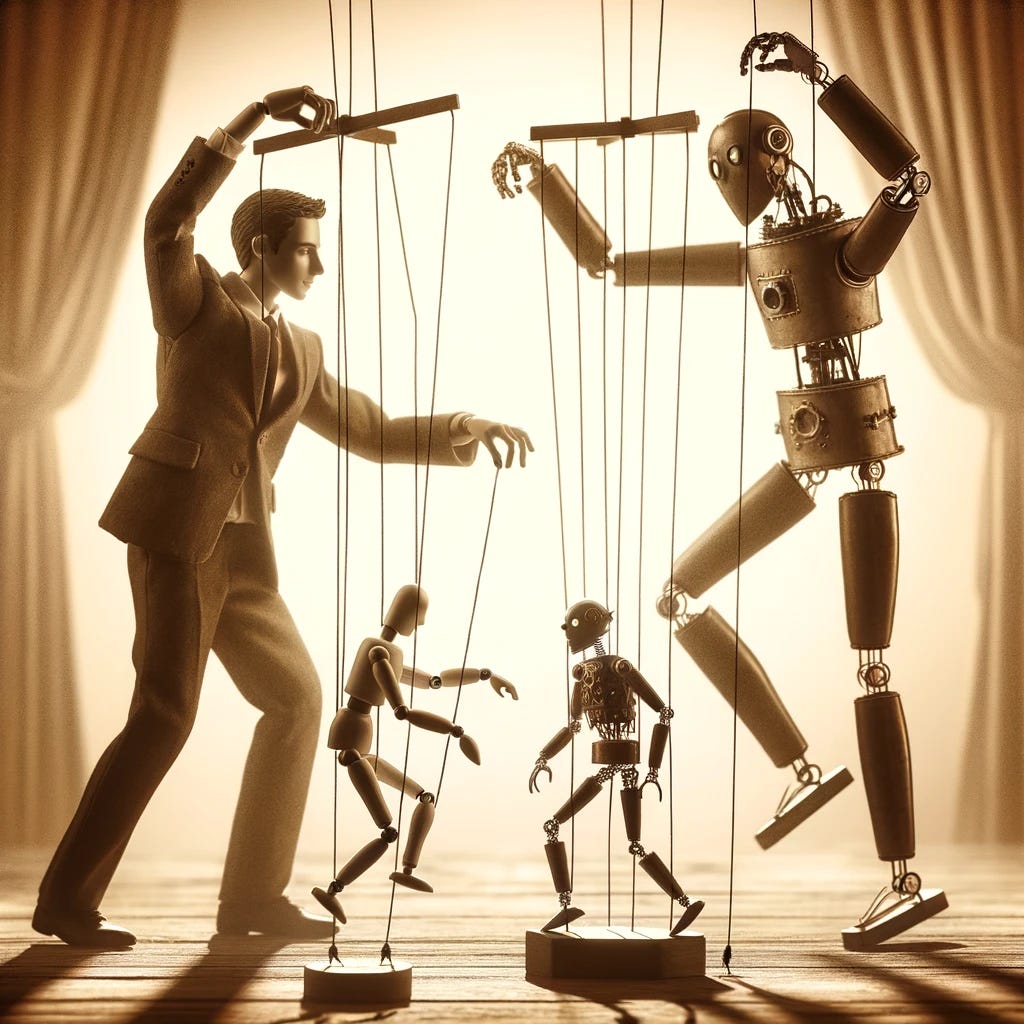

Wang suggests we should be designing AI in a way that requires the integration of human voice and insight. AI needs a human in the loop.

Being a human in the loop means embracing the idea that generative AI is a tool, and because it is a tool, we have agency over it. Schools and individual educators may not have a huge amount of influence over how AI systems are designed, but we do have influence over how we teach students about human-centered use of AI and how to carry that approach with them into an AI world. I think the “human in the loop” concept applies not just to AI’s design, but also to its use in schools.

Learning how to be a good human in the loop aligns well with learning how to nurture and develop agency, a longstanding goal of school. Consider Jennifer Davis Poon’s excellent description of student agency and the competencies associated with it:

Agency + AI = Human in the Loop

So, what could this look like in our uses of AI?

1. Turn personal goals into good prompts. I recently met a teacher who wanted to help his 8th grade students use AI to help them be better project managers. His students were about to embark on an independent capstone research project, and the teacher knew that project management (allocating time, setting benchmarks and deadlines, reporting out on progress) would be a new skill for many of them. So, he created a template for a structured interaction with a chatbot. It included an initial prompt that students could copy and paste into the bot and suggestions for how to nudge it to get responses tailored to the student’s individual project.

I think this is a good example of how to support students in effective use of AI: these students may not know enough about project management to know how to ask AI to help them with project management, but we as teachers do, so we can provide them with language and guidance on how to engage in a productive, personalized exchange.

To learn more about constructing an effective prompt, you can start with Ethan Mollick’s prompt library, OpenAI’s guide to prompting, or AI for Education’s prompt library.

2. Engage AI output actively, not passively. A student told me about how she approached AI in this way. If something she heard in a class was confusing to her, she would go home, take out the notes she had taken in class, and then ask ChatGPT to explain the concept or topic to her as if she was in fifth grade. She would then see if the bot’s explanation clarified her understanding and allowed her to better understand the notes she had taken.

In many ways, this is interacting with AI as one would with a skilled tutor; its ability to instantly explain ideas at a variety of levels can support students in processing information. In addition, the student is not relying on AI as a single source of truth. She has her notes, she has what she remembers from class, and she has her ability to look across those sources to better understand what she is being asked to learn.

How can we as teachers help students distinguish between active and passive use of AI? What prompts or tips can we provide them to incentivize that behavior?

3. Teach and coach AI to be better. When I watch educators and students use AI, I am struck by how often the exchange ends after one prompt and one response. For example, “make a rubric about X for Y class” is not enough information for AI to produce a really good rubric, but I have seen teachers look at the first response and either use it immediately or reject it as low-quality and close the chatbot. Yet one of the most powerful features of AI is that it learns from and adjusts its behavior to our feedback.

This requires some patience and resilience. The work of determining exactly what feedback is needed and how to craft it is challenging: sometimes you need to make multiple attempts, and sometimes you have to start fresh with a whole new conversation to “reset” the bot. But, what you learn from that process is transferable to your future interactions with AI: just as we become better teachers and coaches with practice, so we become better trainers of AI.

4. Make AI inputs and outputs your own. Leon Furze has been doing a very good series on using AI to teach writing, and his ideas and suggested prompts reflect Wang’s emphasis on process over product. Consider this suggested AI prompt from his post on using AI for exploration of texts:

“We are using mentor or model texts as a way of learning the techniques and style of quality writing. Generate an annotation checklist of things we could look for in our mentor texts related to <style, structure, voice, tone, language use, word choice, etc.>”

Students can adjust this prompt according to the kind of mentor text they’re working with (a news article, a blog post, an academic paper, etc.), and generate a checklist that includes elements relevant to their personal goals. Similar to the student who uses ChatGPT to explain complex concepts to her, Furze’s prompts put the learner in the position of having to do something with the output. Evaluate it, compare it to their own thinking, apply it to their chosen text, and consider how it can launch them in new directions.

5. Reflect on the experience. If we use AI with students, we should ensure there is time to reflect on the experience. In my own conversations with students, I find their reflections to be varied and interesting: some talk about “lightbulb moments” that AI enabled for them, others dismiss the output as mediocre and unhelpful, others are trying it in many different ways and landing on a few reliable uses for it, and others don’t like using it at all for ethical reasons or out of fear that they’ll “get caught” using AI and be accused of cheating.

I have written before about Tom Sherrington’s quote that “understanding is the capacity to explain,” and metacognitive work is a simple and powerful way to see if and how students are learning (with or without AI). I’ve also written about how and why we should talk openly with students about AI. Here’s a simple reflection protocol I learned a few years ago from students and teachers at Urban Assembly Maker Academy that we could use as a reflective “check” as students use AI:

What do I know?

What do I need to know?

What are my next steps?

Being a good human in the loop requires knowledge. We have to access prior knowledge to create precise prompts, to evaluate AI outputs, to give AI good feedback, to customize the output to our needs, and to reflect on whether and how AI has been helpful. One of the most frequent concerns I hear expressed by teachers is that using AI will diminish students' interest in and ability to acquire knowledge. The human in the loop framework helps illustrate to students how knowledge supports agency, and that knowing things helps us use tools like AI to make our goals and visions for ourselves a reality.

Upcoming Ways to Connect with Me

Speaking, Facilitation, and Consultation. I’m currently planning for the second half of 2024 (June to December). If you want to learn more about my consulting work, reach out for a conversation at eric@erichudson.co or take a look at my website. I’d love to hear about what you’re working on!

Online Workshops. I’m thrilled to continue my partnership with the California Teacher Development Collaborative (CATDC) with two more online workshops. Join us on March 18 for “Making Sense of AI,” an introduction to AI for educators, and on April 17 for “Leveling Up Our AI Practice,” a workshop for educators with AI experience who are looking to build new skills. Both workshops are open to all, whether or not you live/work in California.

Conferences. I will be facilitating workshops at the Summits for Transformative Learning in Atlanta, GA, USA, March 11-12 (STLinATL) and in St. Louis, MO, USA, May 30-31 (STLinSTL). I’m also a proud member of the board of the Association of Technology Leaders in Independent Schools (ATLIS) and will be attending their annual conference in Reno, NV, USA, April 7-10.

Links!

Teachers are using AI to grade papers. How do you feel about using the tools listed here? How would your students and their families feel?

Amy Choi at Global Online Academy offers some practical and reassuring advice for how to handle and overcome the frustration and dead-ends that can come with working with AI.

ATLIS has put together an excellent AI Resource Guide for independent school boards.

I’m late to this Dhruv Khullar article, but I learned a lot from it: “Can AI Treat Mental Illness?”

“Generative AI is a hammer and no one knows what is and isn’t a nail.”

You asked: How can we as teachers help students distinguish between active and passive use of AI? What prompts or tips can we provide them to incentivize that behavior?

One way is to appeal to their self interest.

A point I make to students is that passive use of AI (I like the active vs passive distinction btw) is unlikely to help them produce the best work they can, but that active use of AI could help them achieve more, both compared to current peers and to previous generations.

The problem is that whilst this may incentivise the very best students to think carefully, it is hard to hide the fact from the less motivated, that (assessment design withstanding) they may be able to move from poor to average, or even average to good grades, with some fairly passive Ai use.