Looking Ahead with AI, Part 2: Students

Literacy, Learning, Ethics

This is part two of the “Looking Ahead with AI” series. You can find part one, about teachers, here and part three, about school leaders, here.

We cannot control if and how students use AI.

If we view AI as an “arrival” technology (like smartphones or the internet) and not as an “adoption” technology (like smart boards or learning management systems), then we should recognize that we are not in a position to decide if AI should be in our schools or not. Like the arrival technologies that preceded it, AI is and will become deeply integrated into our lives, often in ways we are barely aware of. Students (and everyone else who works in a school) will use AI regardless of a school’s position or policies.

Looking ahead to how we want to engage students on AI in the coming year, we should focus less on controlling their use of AI and more on nurturing their autonomy. As Rosetta Eun Ryong Lee argues in her “Young Person’s Guide to Autonomy”, decision-making is a core competency of autonomy.

When it comes to AI, what do students need to know and be able to do in order to “choose wisely”? How can we engage students on AI in a way that helps them practice making good decisions about it?

I think there are three possible areas of focus: literacy, learning, and ethics.

A note on the role of families: I speak to parents and guardians about AI, and they can be (and are eager to be) partners and resources on these topics. But, many lack knowledge and confidence when it comes to talking about AI. Schools should be offering educational opportunities on these topics for families. What’s more, any of the ideas below can be used by parents to start conversations with their children.

Literacy

Consider how

defines effective use of AI in her presentation “AI for Research Assistance: Skeptical Approaches”:To successfully work with generative AI

You ask it for what you want.

Then you question what it gives you. You revise, reject, add, start over, tweak.

To do this, you need

critical thinking, reading, and writing skills.

subject-matter expertise.

knowledge of what kinds of weaknesses to look out for in AI. Let’s call that critical AI literacy.

Most students I talk to are still figuring out when and how to effectively ask AI for what they want (“prompting”), and they don’t spend much time coaching or refining AI output through dialogue. More importantly, they often don’t know enough about 1) the subject or 2) AI in order to critically evaluate the output. How can we help students become aware that these skills and knowledge matter? How can we help them build that knowledge and those skills?

One way to address this issue is to bring AI into school for some simple literacy exercises. Teachers I meet are doing variations of what I call an “AI Vulnerability Test.” They project an AI chatbot on the screen in their classroom and feed it one of their assignments. Then, they work with students on a series of questions (this is extra valuable if you do the same prompt across multiple chatbots to illustrate differences) :

Is AI accurate in its answer? How do you know? If you don’t know, what do you need to do to find out?

Where did AI get this information? How did it compose this response?

What grade would you give AI for this output? What follow-up questions or feedback should we give it to make it better?

How could you do better than AI on this assignment?

If AI can do a pretty good job on this assignment with just a prompt or two, what’s the point of this assignment?

Proactive approaches like this, rather than the reactive approach of talking to students about AI only when they’ve been caught using it to cheat, allows schools to influence behavior through learning rather than punishment.

It also allows them to reach more students. As a student once put it to me, “The people who get caught are just the people who are bad at AI.” Doesn’t seem like a scientific study to me, but the core truth resonates: far more students are experimenting with AI than we are aware of, and all of them need to be critically literate.

Learning

My conversations with teachers have shifted from conversations about “cheating” to conversations about “struggle.” They are concerned that the vast majority of generative AI tools are designed to eliminate friction in our lives, to help us offload cognition to a bot. And they’re right to be worried. As

lays out clearly, friction is a critical component of the learning process, and AI is a threat to “frictional” tasks like close reading and analysis.These conversations also remind me that students are already quite familiar with struggle. They have done things that are hard and they know what it takes to do things that are hard, sometimes in school, sometimes outside of it. When a challenge sparks their interest, or when the stakes are real to them, or when they feel a sense of success and support when presented with difficulty, they are more likely to invest in the struggle.

I often wonder if this AI moment is a moment to explicitly teach students about how learning happens, to connect their experiences with struggle to the psychology and neuroscience about how learning happens. I believe adolescents are capable of and would benefit from learning about what research tells us about desirable difficulties, the difference between learning and performance, and looking for meaning and story in their work. (This would require, of course, that educators know the same and have designed assessments that align with these principles).

When I speak to students, I show them AI use cases from a variety of schools. I ask them, is this cheating or is this appropriate assistance? Their answers vary to a surprising degree, but they boil down to the same core ideas: 1) students know it’s bad for AI to do all of their work for them, but 2) they are curious about how it can be a helpful learning assistant (the way a tutor or a parent can be a form of assistance), and 3) they want guidance from their school about how to know the difference.

Ethics

AI ethics is a topic where I’ve found educators and students share the same concerns, but they don’t necessarily know that they share them.

Both are concerned about academic integrity. Educators do not want students to cheat the school or themselves by misrepresenting their own work or by bypassing productive struggle. Students do not want to cheat, nor do they want to be falsely accused of cheating with AI because their school is hypersensitive to AI or hasn’t offered clear guidelines for use or is using unreliable detection software.

Looking ahead, we should work with students to shift the culture of mistrust around AI and academic integrity. I have written before about how trust is built and how it is broken and repaired. Policy does not build trust. Dialogue does. Start a conversation with students about AI. Begin with a few very simple, curious questions that students and educators can ask each other: “How do you use AI? What do you think of it? What excites you about it? What worries you?”

In addition, the field of AI ethics is so much broader and deeper than academic integrity, and this is a strong point of connection between educators and students. Both groups are deeply troubled by issues of bias, environmental impact, labor, privacy, and intellectual property. By simply using AI (as with so many other things in modern life), we are engaging in a number of ethical tradeoffs. Knowing about those tradeoffs helps us make better decisions about if, when, and how to use AI.

For those educators who don’t feel confident or comfortable using AI with students quite yet, exploring AI ethics is a meaningful learning pathway. Think about the ways you ask students to discuss current events, to wrestle with ethical dilemmas, to stage debates, to complete research projects, etc. Append the term “AI” to these activities, search some reliable media sources, and you will find a deep well of high-quality journalism, research, and thinking on a multitude of topics to have a meaningful, open discussion about ethical decisions about AI.

Start Small

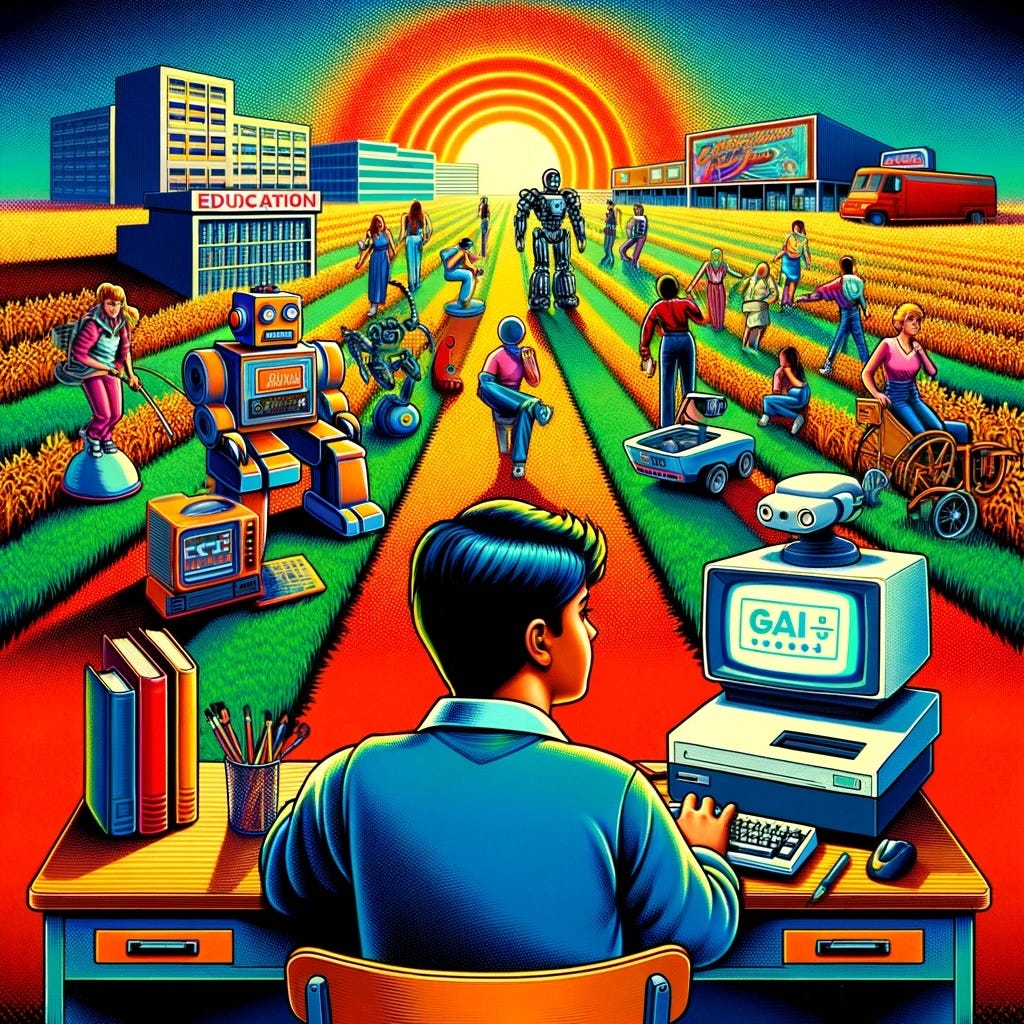

I like

’s take that “We need more useful little ideas for using generative AI in classrooms IMO and fewer useless big ideas.” He offers this tweet from Spanish teacher Matt Miller as an example:Doing something like this with students and then reflecting on it together can touch on literacy, learning, and ethics. How do we prompt AI to create these images? How does it create these images? What are we learning from this process vs. what is AI doing for us? Is it ethical to create and learn from images like this? What are the tradeoffs when we create images like this?

As Lee says, developing autonomy is not a one-time event: “Adolescence is a transitional time when you practice decision making - when you need help and when you can do it on your own, when you need information and when you want advice, when you need adult support and when you want peer support.” Imagine the impact on students if all of us, in our various roles, found useful little AI ideas to explore with them in the coming year, ideas that empowered them to make wise choices.

Upcoming Ways to Connect with Me

Speaking, Facilitation, and Consultation. If you want to learn more about my school-based workshops and consulting work, reach out for a conversation at eric@erichudson.co or take a look at my website. I’d love to hear about what you’re working on!

AI Workshops. I’ll be on a team of facilitators for “AI, Democracy, and Design,” a design intensive for educators being held June 20-21 in San Jose, CA, USA (offered via CATDC).

Leadership Institutes. I’m re-teaming with the amazing Kawai Lai for two leadership institutes in August (both offered via CATDC): “Cultivating Trust and Collaboration: A Roadmap for Senior Leadership Teams” will be held in San Francisco, CA, USA, from August 12-13 and “Unlocking Your Facilitation Potential” will be held in Los Angeles, CA, USA, from August 15-16.

Conferences. I will be facilitating workshops on AI and competency-based education at the Summit for Transformative Learning in St. Louis, MO, USA, May 30-31 (STLinSTL).

Links!

Five questions every parent should ask their child’s school about AI.

I learned a lot from this interview with Meredith Whitaker, the president of Signal Foundation. She weaves together the technical, business, political, and ethical elements of AI (and tech in general) in a very compelling and accessible way.

OpenAI has released its “model spec,” a document that outlines how it wants ChatGPT and its other products to behave. Be sure to scroll down to the examples; they are illuminating.

Rest of World is doing interesting journalism on AI: it’s tracking AI’s impact on elections worldwide, noting the an AI education gap in Africa, and exploring how people in China are using “deathbots” to help them grieve.

“Most of the undergrads now at Berkeley and elsewhere watched the murder of George Floyd on their phones when they were in high school. They saw that the narratives put out by the police and by the media did not match what they were seeing with their own eyes. They had their high-school graduations cancelled by covid, and started college on Zoom, and contended with the seeming possibility that the pandemic would end society as they knew it. Sitting in their bedrooms, they sunk deeper online, as the rest of us did. A shunt of disbelief opened up… The war in Gaza has taken that shunt of disbelief and ripped it wide open. They don’t trust us anymore.” Jay Caspian Kang on student protests.

All companies which are trying AI in generating subject content are hiring only PhD candidates to evaluate the quality of the response. It indicates that just some subject matter expertise won't help. You need deep understanding to do a critical analysis of the AI response. Not all children have this level of critical thinking. So, AI literacy is essential in the coming Era.