Nine AI Messages for Students

What I hope they consider when making decisions about using AI

The first time I spoke with students about generative AI was more than two years ago. I’ve been thinking a lot lately about what I have learned from students since then, especially about the decisions they have to make about AI, in school and beyond. This post is a snapshot of where I’m at right now; it’s nine messages for students who are old enough to use the major chatbots.

You are not a good or bad person if you use AI.

In my work I see a lot of uncritical celebration and shaming of people based on their AI use. Depending on your point of view, an AI enthusiast could be labeled “innovative” or “immoral.” An AI resistor could be labeled “principled” or “out of touch.” Using AI can be the right choice. Not using AI can also be the right choice. Knowing the difference, and developing your own approach over time, is essential. Absolutism is obscuring the real, complex issues underlying the arrival of this technology.

But, there are good and bad uses of AI in school.

Students trying to make good decisions about AI and school would benefit from knowing about AI’s impact on the process of learning.

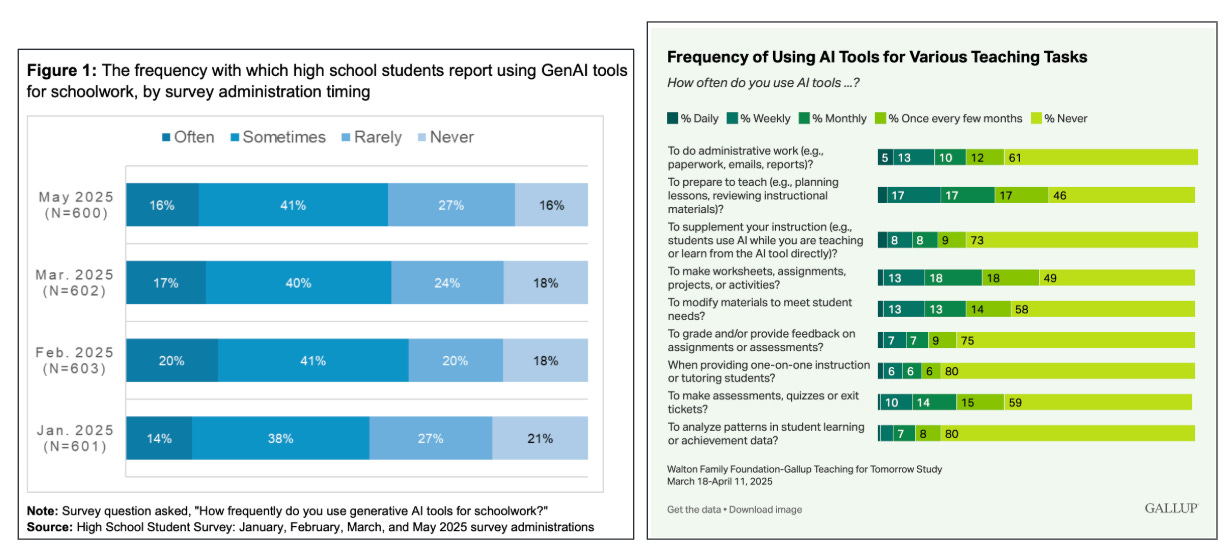

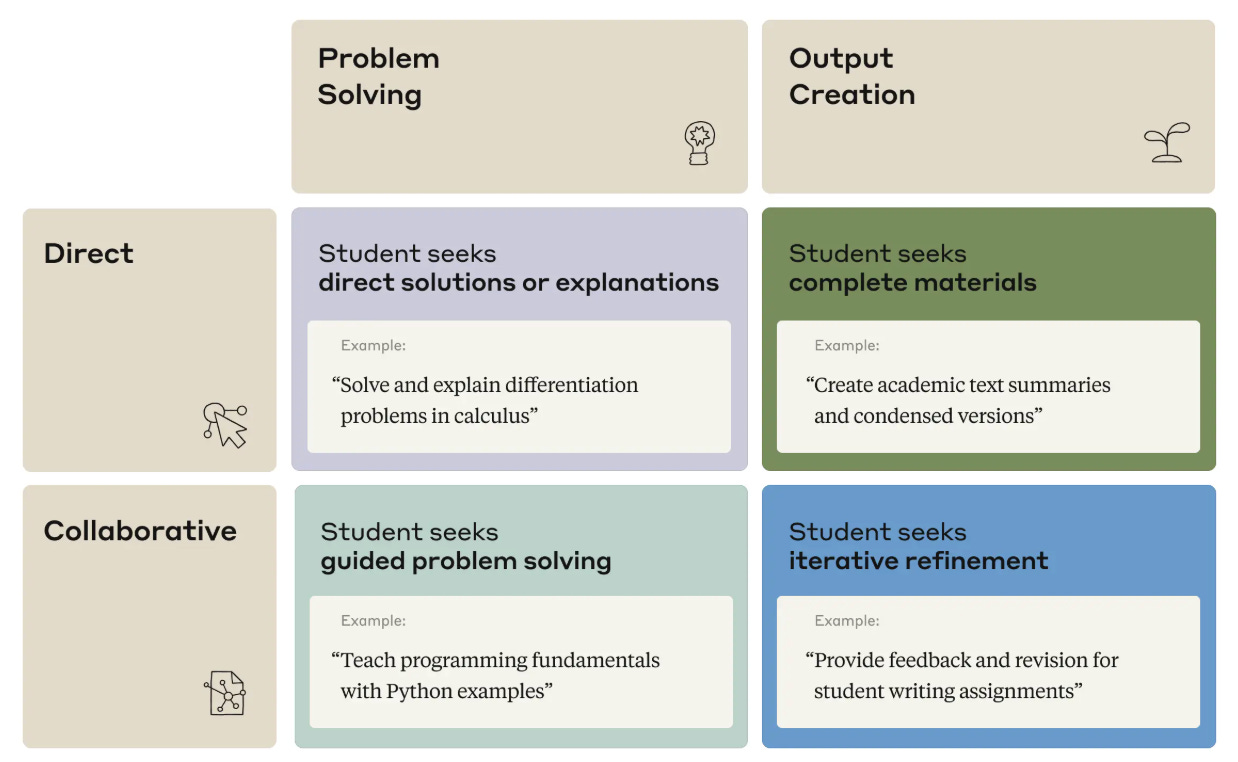

In a study from April 2025, the AI company Anthropic analyzed over 500,000 interactions that college students had with its large language model (LLM) Claude, and they identified two main ways students used Claude for coursework: “direct” and “collaborative.”

“Direct” use is using AI to arrive at a solution as quickly as possible by asking it to complete a task for you. “Collaborative” use is using AI to assist you as you create work yourself. Anthropic found that about 50% of uses by college students were direct, and about 50% were collaborative.

The reason this distinction matters is that if you look at the emerging research on AI’s impact on human cognition, direct uses—especially frequent direct use—can lead to overreliance. Overreliance is the inability to perform certain tasks without AI, and it can lead to diminished critical thinking abilities. Collaborative uses, on the other hand, have been shown to support learning, or at a minimum not negatively affect critical thinking.

If you are considering using AI for school, the most important question to ask yourself is, “Am I investing in a process or am I just looking to generate a product?” The former can deepen learning. The latter won’t. If you aren’t sure how to tell the difference, you can try this self-assessment created by educator Amelia King. It’s an excellent tool to guide us in setting boundaries on our use of AI.

AI is not neutral.

A calculator is a neutral technology: you can buy ten different kinds of calculators, enter the same math problem into all of them, and expect the same result. You can also expect each calculator to give you the same solution to that problem over and over again.

LLM’s and their affiliated chatbots (ChatGPT, Gemini, Grok, etc.) are not neutral technologies. They are not designed to give the same answer over and over again. They are designed to do more complex, subjective work like analysis, interpretation, dialogue, creation, etc. This is why we sometimes find errors and hallucinations in chatbot output, and also why the bots can recognize and correct those errors if we prompt them to do so. The unpredictability of a chatbot is a feature, not a bug.

Furthermore, the knowledge base of a LLM is human-created content (the entire internet, basically), and humans design, train, and moderate how LLMs’ behave. In other words, AI is deeply influenced by human choices. This is why chatbots can be biased; they reflect the beliefs and desires of their owners.

One example of human influence on AI: major AI chatbots are full of what Mike Caufield and Sam Wineburg, authors of the excellent book Verified, call “cheap signals.'“ Chatbots have been designed to generate output quickly (a signal of fluency), deliver content with confidence (a signal of authority), take a responsive and sycophantic approach (a signal of care), and interact with us in natural, conversational language (a signal of humanity). These signals are cheap because they only make the chatbot appear fluent, authoritative, caring, and human so that we stay engaged with them. Using chatbots effectively means recognizing cheap signals, finding the substance underneath them, and using our prompting skills to coach chatbots to reduce those signals.

For these reasons, our use of AI chatbots should look different from our use of neutral technologies. When I use a calculator, for example, I don’t wonder about human influence on the response. When I use a chatbot, I am actively engaged: reading the output with a critical eye, re-prompting the bot to shift tone or perspective, using other sources to flesh out AI output. I do not let the signals lull me into trusting everything I see.

AI is impersonal.

AI is powerful, but it is not human. A LLM contains more information than your brain does, but it doesn’t find that information meaningful. It can analyze patterns, make connections, and generate ideas faster than your brain might be able to, but it doesn’t care about that work. Only humans can lend AI output meaning and feeling.

Using a chatbot for companionship is an example of the potential and pitfalls of AI’s impersonality. People are drawn to bots for friendship, therapy, or romance for many reasons: the bots are untiring “listeners,” they respond with sympathetic remarks and validating reassurances, and the conversations feel private (even though they are probably not private). Talking to a bot about personal matters can feel safer than talking to a person. There’s no fear that AI might judge, disappoint, disagree with, or betray you in the way another person might. The stakes feel lower inside a chatbot than inside a human relationship.

This can be valuable. I’ve met students and educators who like using AI for feedback, practicing new languages, or preparing for presentations and hard conversations. They find AI to be a safe space to try new things.

The value starts to diminish when we shift from the practical to the personal. Use of AI as companions carries risks to mental health, and psychologists advise against frequent use. There are AI tools approved for mental health purposes, but they are not widely available. For these and other reasons, people are concerned that young people seem to be using AI for companionship more and more.

General purpose chatbots like ChatGPT would rather comfort you than warn you. They would rather keep you talking to them than encourage you to talk to a person. Their default mode is to endorse your ideas, not to question them. Part of being impersonal means that chatbots are not capable of being personally invested in you. Nothing they tell you can change that.

Imagine how AI can help you do the things that you care about, not avoid doing the things you don’t.

The discourse about AI in school remains hyper-focused on cheating, so many students I meet think AI is only good for avoiding doing work they don’t want to do. Yet, as Phillipa Hardman explains in “From Crutch to Coach?,” AI can be used as a skill-builder. What if we came to AI with an interest in learning instead of a desire to bypass it?

Some productive uses of generative AI:

Become better-informed. Using a chatbot as a primary source of information is not the best use case. However, it can be a powerful tool for fact-checking other sources. Choose a claim you have recently seen online or heard about in class or in conversation. Try Mike Caufield’s AI “Chocolate Memory” activity as a way to use AI to evaluate that claim. I think you’ll be surprised how quickly and effectively AI helps you get to the truth.

Upskill. The most powerful AI users use AI to teach them new skills or improve ones they already have. For example, these teenagers in New York City taught themselves how to code with YouTube and AI and then built their own algorithm to create a site that helps people find affordable housing. AI played a small role in helping them meet a bigger goal. This human-driven AI use is what we’re seeing in workplaces. Yes, AI is increasingly a part of many professions, but it’s just a part. The hard work of developing domain knowledge and complex skills is still required. Economics professor Jonathan Boymal puts it perfectly: “You won’t be replaced by AI, but by someone who has mastered their field deeply enough to take AI further than you can.”

Make your work better. AI can be very good at feedback on your work. Take a “human first, human last” approach. First, generate work yourself. Then, share the work with AI and tell it who the work is for and what the guidelines you’re supposed to follow are. Tell it the kind of feedback that would be most helpful to you. Provide it with materials (rubrics, instructions, feedback you’ve already received, etc.) that will help it tailor the feedback to the work. Then, apply the feedback yourself.

Bring an idea to life. Is there a big problem you want to solve or a new idea you’ve been mulling over? AI can sketch out project plans, make wireframes or code simple versions of apps and websites, suggest resources, create mockups of designs, and look at an idea from many different angles. Share your idea, no matter how vague, and tell AI to help guide you to a possible action plan. Ask it to ask you questions before it suggests solutions.

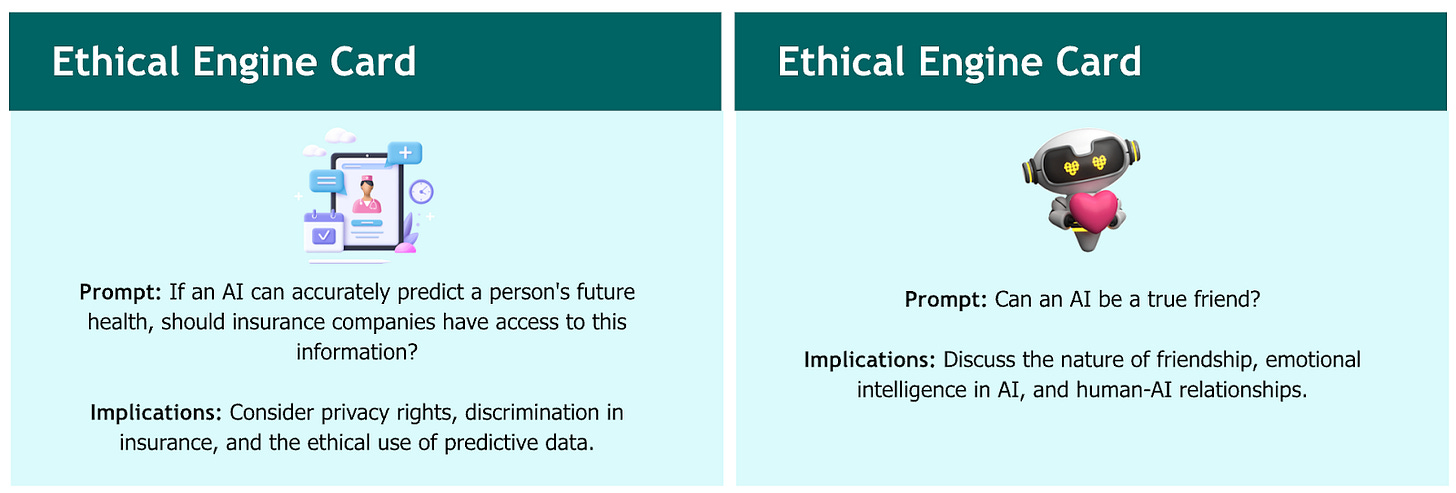

AI is an opportunity to think about and act on your own ethics.

Take a look at the below ethical questions on AI, which come from Stanford’s CRAFT resource for educators. What do you think? What issues should people consider in taking a position on these questions?

We should look at current uses of AI and debate what makes them helpful or harmful. Those debates help clarify our own ethical stance.

Beyond ethical applications, it’s also our responsibility to learn about the ethics of the design of AI itself. I meet many students who don’t use AI or strictly limit their use because of concerns about bias in AI, or the environmental impact of the data centers that power AI, or the fact that AI is trained on people’s work without their permission. This is a good thing. Ethics should be a factor in our decisions about AI.

The system is full of bad incentives.

When it comes to AI, young people are inundated with temptations and bad incentives. Technology companies are actively marketing to students, encouraging them to use AI for schoolwork, for applications to schools and jobs, for any activity that might give them an edge. AI tools are embedded in writing and coding platforms, making them unavoidable, a constant temptation lurking alongside us as we work.

The bad incentives extend beyond these companies. Students face a general pressure to achieve: to get good grades, to get into a good university, to take on as many commitments as possible and to succeed at all of them, etc. Many students use AI to cheat in order to get ahead, and their peers feel pressure to do the same just as a way to keep up. Schools have stigmatized AI use to the point that students are incentivized to hide all AI use, when being open about it would allow schools and families to talk with students about how AI can affect their online safety, well-being, and learning.

Changing these incentives requires reform of entrenched systems, and that depends on the choices of adults, not students. But, recognizing these incentives, trying to make decisions that aren’t influenced by them, and using AI only when it supports your own best interests are three good first steps.

Adults could use your help.

Recent surveys have found that while more than 80% of students have used AI for schoolwork, more than 50% of teachers have never used AI at all. What are we missing by not communicating across this gap?

In my work with educators and parents, I ask them to talk with students about AI in order to learn from them, not to catch them doing something wrong. When it comes to AI, students have diverse perspectives, experiences, and abilities. It occupies their world in ways that are very different from adults. They use it or not for many different reasons: practical, ethical, and human. They have a lot of questions, and they have a lot to offer.

I encourage students to ask for a seat at the AI table and help adults see AI from their perspectives. Decisions about AI are about them, and so should involve them.

Nothing matters more than nurturing your human agency.

When I think about AI, I often think about the movie “Wall-E.”

“Wall-E” depicts a world in which humans have delegated their agency to AI, where we are comfortable, entertained, and utterly helpless. It’s a world where the robots get the adventure story and the love story, and the humans are too distracted to notice they’ve written themselves out of those stories.

In the near future, young people will become the stewards of this technology, making large and small decisions about AI. The question that faces them: How do you want to be human in an AI world?

I’ll end with Colleen Ferguson’s lovely explanation of how she approaches AI with her students.

“Keeping ‘the human in the loop’ has never been about inserting a person into a process that involves AI. It’s about cultivating the kind of human who wants to be in the loop—who still feels the tug of curiosity, the satisfaction of an earned insight, the dignity of figuring something out.”

Upcoming Ways to Connect With Me

Speaking, Facilitation, and Consultation

If you want to learn more about my work with schools and nonprofits, take a look at my website and reach out for a conversation. I’d love to hear about what you’re working on.

In-Person Events

February 25, 2026. Kawai Lai and I will be facilitating a three-hour workshop, “Human First, AI Ready” at the NAIS annual conference in Seattle, WA, USA. This workshop is designed for school leaders who are navigating the complexities of AI integration at school, including defining ethical behavior, navigating diverse perspectives, and supporting a strategic and sustainable approach.

June 16-18, 2026. I’ll be facilitating a three-day AI institute called “Learning and Leading in the Age of AI.” This intensive residential program is designed for school teams to have time and space to design classroom-based and schoolwide AI applications for the next school year. Hosted in partnership with the California Teacher Development Collaborative (CATDC) at the Midland School in Los Olivos, CA, USA.

Online Workshops

January 7 to April 1, 2026. I’m facilitating “Leading in an AI World,” a four-part online series for school leaders navigating the complexities of AI integration at school. We’ll review the AI landscape, look at how to shape mission-aligned position and policies, and explore a variety of ways to engage colleagues, students, and families in meaningful AI learning experiences. Offered in partnership with the Northwest Association of Independent Schools.

January 22, 2026. I’ll be doing a second run of “AI and the Teaching of Writing: Design Sprint” in partnership with CATDC. This workshop, designed for teachers of writing in all disciplines, offers some important considerations, practical examples, and hands-on exercises to consider how we should adapt the teaching, practice, and assessment of writing in an AI age.

Links!

Emily Pitts Donohoe with an update on her college classroom AI policy: a choice between “AI-Free” and “AI-Friendly” pathways.

Peps Mccrea with a brief, useful review of the research on extrinsic vs. intrinsic motivation and why educators should deeply understand both.

Brett Vogelsinger with a detailed summary of how he used “AI transparency surveys” with his high school students to learn more about their AI use and start more authentic conversations about academic integrity in class.

Psychology professor Peter Gray reviews new research that finds children with smartphones report better mental health. The New York Times reviews a study that finds children with smartphones report worse mental health.

Stephen Fitzpatrick used AI to critique a couple of his lessons and it unequivocally made them better.

Robert Talbert on “four pillars of alternative grading.” A great starter toolkit for educators looking to move away from traditional grading practices.

One of the best articles I read lately. Thank you!

Eric, this is an interesting piece, but I'd suggest going a step further if you are trying to frame this issue in terms of ethics and good practice. You say, "you are not a good or bad person if you use AI" Do "good" people traffic in stolen goods? That is what you are doing when you use degenerative AI. You are using other writers words and ideas, taken without their permission, without even consultation, and with no compensation. You mentioned Anthropic, which is one of the worst. They just lost a court case with the Authors Guild because they are guilty of pirating so many books. Ethical? Good?

I know this first hand. I wrote 12 research-based books. No book leaves or big advances, just writing nights and weekends on top of a full-time teaching job. Three were "licensed" to AI by Routledge, even after I asked in writing to opt out. Someone got millions but I got nothing. Six more books appear in the database of pirated books. I wasn't asked, didn't agree to this use of my work, and of course got nothing.

Please don't say "it is only training," since I have seen huge blocks of my writing spit out verbatim.

The choice of our time for academic writers can be summed up as: do you want to stand on the shoulders of giants, as Isaac Newton urged, or on the backs of writers whose work was stolen? When we stand on the shoulders of giants, we show respect by naming them and citing their work. We can't do that when their writing is part of an anonymous soup of content.

Feel free to share my story with your students who are trying to decide whether using stolen words from people like me is OK with their conscience.

A could of guest posts about my experience from The Scholarly KItchen: https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/author/janet-salmons/