What Schools Are Asking About AI, Part 2

An update on the questions I'm hearing and the answers I'm offering.

I collaborated with the team at Flint to select the questions that appear in this article. You can find the original post on their blog.

A few months ago, I wrote a post sharing some of the common questions and answers that were coming up in my travels to schools and conferences. I’m in the middle of another burst of AI engagements, and I’m happy to find schools are diving more deeply into AI and making longer-term decisions about how to approach it. This shift has raised new questions (and rejuvenated some old ones), so I thought it was time for a sequel.

I have serious ethical concerns about using AI. Why should I still learn how to use it?

The ethical issues embedded in the design, growth, and maintenance of AI systems are deep and concerning: algorithmic bias, environmental impact, intellectual property concerns, labor practices, and data privacy are just a few of the problems we must confront when a tool this powerful develops as quickly as AI has. I’m meeting more and more people who are “conscientious objectors” to AI: they do not use AI because, for them, the ethical implications of embracing it outweigh any potential benefits.

Objecting to AI on ethical grounds is valid and important. Ignoring it on ethical grounds is not. If the purpose of school is to prepare students for the world beyond it, then we have a responsibility to talk with students about AI and its impact on their present and future lives.

The good news is, we don’t have to be power users of AI in order to teach students about AI. I invite teachers to bring their ethical concerns into the classroom in order to model and teach students how to become critical users of AI. Examining case studies, debating the issues, and critically evaluating AI-generated content are all important ways to help students develop their own positions and make better decisions about AI. Maha Bali has been writing about critical AI literacy for over a year and has gathered many useful resources. Leon Furze has an excellent resource for teachers called Teaching AI Ethics.

If AI does more and more work for teachers, what does that mean for the future of teaching? What is the role of teachers in the future?

In October, I was in the audience for a panel discussion of Silicon Valley executives who were discussing the impact of AI on education. One panelist cited this scene of a Vulcan school from a 2009 Star Trek movie as a potential model:

The utopian interpretation of this: a sophisticated, personalized tutor for every student. The dystopian interpretation of this: every student going to school in a pit lined with screens. However you feel about the clip, I think it reveals that the companies which design and maintain AI systems are focused on tutoring and personalized learning.

When we think about what this means for the future of teaching, we have to remember that school is much more than tutoring. As Matthew Rascoff of Stanford University has said, “School is learning embedded in a social experience.”

An AI tutor could effectively replicate some core functions of teaching like instruction, differentiation, or assessment. The role of the teacher in an AI future, then, may be to become the protector and steward of the human elements of education. The teacher’s expertise could be used to identify where AI capabilities end and human ingenuity and empathy should take over. Or, to help students apply what they learn from interactions with AI to collaborative projects that have a real-world impact. Or, to provide mentorship and coaching in a way that weaves together knowledge with social emotional learning.

The future might be unclear, but I do think teachers should be learning how to be responsive to AI rather than how to compete with it.

How can teachers regulate what AI knows? To what extent should they micromanage the information AI outputs?

As teachers learn more about how to use AI, they ask me more questions about how they can control it. They want to know if a bot can be trained to become their avatar, delivering instruction, feedback, and assessments in the exact same way they do. They want to know if they can limit a bot’s knowledge to only materials they provide to it. They want to know if they can micromanage outputs to ensure it reflects what they want the student to see.

You cannot control what AI knows and what every output looks like. Generative AI doesn’t have a warehouse of preset responses: you can input a prompt into a model ten times and get ten different responses. Bots also have context windows that limit the amount of information they can take in and hold, so they won’t be able to hold the same amount of knowledge and experience you have as a teacher.

Rather than try to control AI, we are better off learning how to work with it in more targeted ways that augment, but don’t replace, our own teaching process. Use AI to synthesize data or documents, to refine feedback, to generate questions or counterarguments. When we understand AI’s limitations and capabilities (and ensure our students understand them, too), we will become more effective in our work, even if we can’t fully control AI.

What should we be aware of when it comes to selecting, purchasing, and using the many AI tools available right now?

For this question, there are two perspectives to consider: what an individual user should do and what an institution like a school should do.

For an individual, you should be omnivorous: explore widely and freely. The use cases for these tools are expanding rapidly, so we should be flexible rather than focused on finding a single solution. And, most of these tools still offer some level of access for free, so it’s worth experimenting. Use the same prompt across different models and tools to see which generates the best output. Take the output from one bot and enter it into a different one to see if it can be improved or even reimagined. Keep an eye on the major models (GPT, Gemini, Claude, Llama, etc.) rather than the more specialized AI tools. Updates to the models will be a leading indicator of AI’s evolving capabilities.

If you are going to spend money, spend it on the most flexible tool you can find. Right now, this is probably ChatGPT Plus for $20 a month, which gives you a variety of multimodal capabilities and access to one of the best models on the market. Even if you pay for an AI tool, stay open. I pay for ChatGPT Plus and still use Gemini, Claude, Adobe Firefly, and other tools regularly.

If you are trying to make decisions for your school, then you should have two things in place before purchasing an AI solution: 1) a clear, well-articulated rationale and strategy for adopting that tool and 2) a contingency plan for what to do when that tool is no longer relevant and/or its design and terms of use change. Schools are notorious for carrying a large number of “edtech solutions” that are purchased and then languish, applied sporadically or only by a small group of power users. It would be worth reflecting on previous edtech investments and considering what went well and what did not go well, then applying that learning to decisions about adopting AI tools.

If nothing else, ask vendors some basic questions:

What is the involvement of education professionals in the development and updates to this tool? Does the company partner with schools, educators, and/or students in making design decisions?

What advances in AI do you anticipate on the horizon? In what ways will those changes improve this tool? In what ways could they render this tool obsolete?

What is in the pipeline for updates and new features for this tool? How do you make those decisions?

How should we communicate with families about our school adopting AI? Namely, will parents think that we’re outsourcing the work of teaching to AI? And what are they worried about when it comes to their children using AI?

I am spending more and more time speaking to families about AI, and I have the same takeaway as I do when I work with educators, students, leadership teams, and boards: their knowledge of and opinions about AI are quite varied. Any collaboration between schools and families on AI should have an educational component. Aligning on definitions of terms, the current state of the industry, and concrete examples of AI applications at schools is really important to having a meaningful conversation.

Parents do not have a positive reaction when I describe AI tools that help teachers grade papers or generate teaching materials. This is similar to the reaction of teachers when I share how students can use AI to get feedback on their work, refine their writing, clean up code, or study for tests. It’s also similar to the reaction of students when I show them how teachers can use AI to write college recommendation letters or narrative reports. In other words, we are deep in a period of adjustment to AI’s impact, and we are all carrying skepticism and worry. It is going to take time to reset our expectations and understanding of school in an AI age, and demonstrating empathy and care should be our first priority.

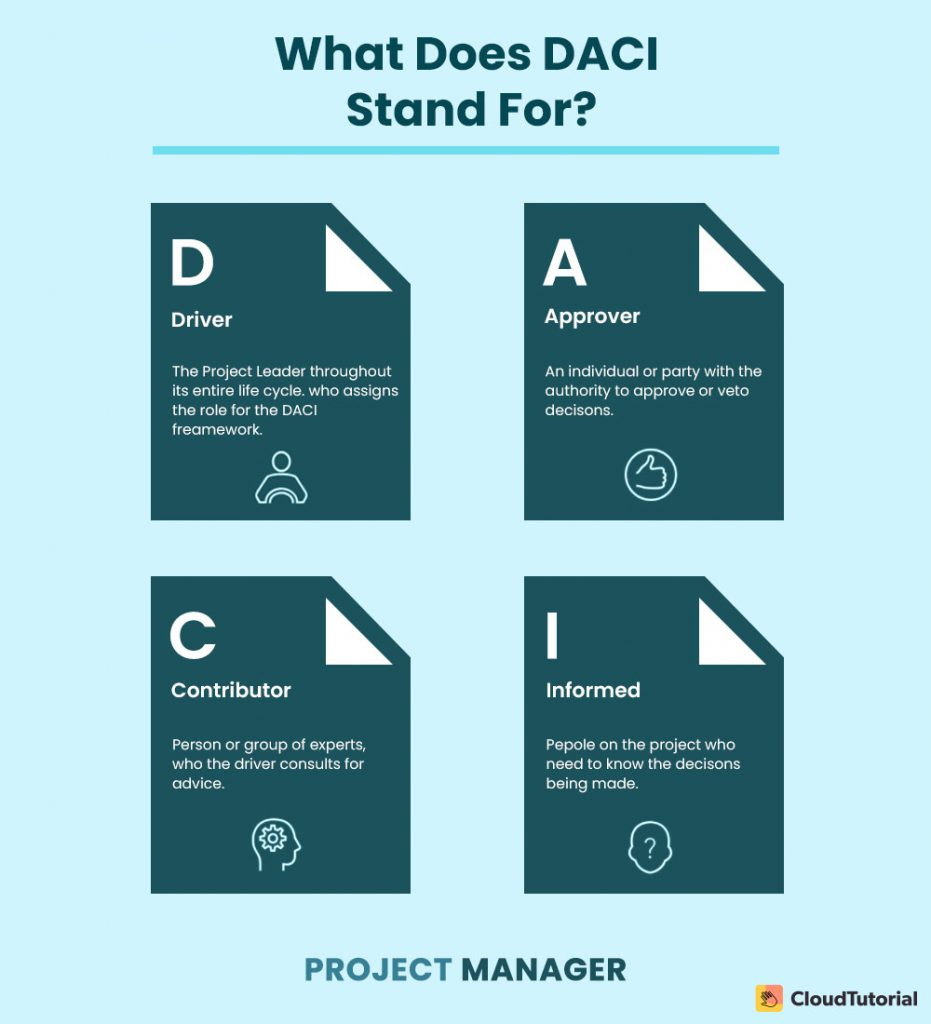

When engaging parents in conversations about AI at school, I recommend thinking about the DACI decision-making framework:

Decisions about AI at school should be driven and approved by the education professionals who work at the school. Parents, however, can and should play an important role as contributors. First, they have an important stake: their children will be directly affected by the decision. Second, parents are an undervalued connection to the world beyond school; their careers, networks, and experiences are resources schools can use to understand how AI will affect students’ futures.

Above all, families want clarity. They want to know that schools have a confident grasp of what AI is and why it’s important to both learning and wellness. They want to know what school expectations for student and teacher use of AI are. They want to know how they can help.

What’s next for schools and AI?

I recently facilitated a strategic foresight workshop on AI for the board and senior leadership team of an international school, and I appreciated this comment from the board chair during one of our planning calls: “I want us to generate questions, not answers.”

I think this could be a mantra for schools when it comes to the future of AI in education. We are not experts, we are investigators. I have written before about what an inquiry-based approach to AI can look like, and while I recognize and have deep empathy for the daily challenges AI raises in schools, I think we have to be open to the fundamental changes it might bring to the core elements of our work. This means learning as much as possible about how early adopters are using the tool in and beyond school, capturing the questions that people are asking, generating big questions of our own, and recognizing that we are watching a major technological innovation unfold in real time.

What are the skills we can bring as educators that help us and our students navigate uncertainty at a time of great change?

Upcoming Ways to Connect with Me

Speaking, Facilitation, and Consultation. If you want to learn more about my school-based workshops and consulting work, reach out for a conversation at eric@erichudson.co or take a look at my website. I’d love to hear about what you’re working on!

AI Workshops. My partnership with the California Teacher Development Collaborative (CATDC) continues with an online workshop on April 17, “Leveling Up Our AI Practice,” and an in-person design intensive for educators, “AI, Democracy, and Design” from June 20-21. Both are open to all, whether or not you live/work in California.

Leadership Institutes. I’m re-teaming with the amazing Kawai Lai for two leadership institutes in August (both offered via CATDC): “Cultivating Trust and Collaboration: A Roadmap for Senior Leadership Teams” will be held in San Francisco, CA, USA, from August 12-13 and “Unlocking Your Facilitation Potential” will be held in Los Angeles, CA, USA, from August 15-16. Both are open to all, whether or not you live/work in California.

Conferences. I will be facilitating workshops at the Summit for Transformative Learning in St. Louis, MO, USA, May 30-31 (STLinSTL).

Links!

I had a great conversation with Sean Dagony-Clark on the “Ways We Learn” podcast. We talked about what I’m seeing in my work with schools when it comes to policy and teaching decisions about AI.

A really funny and engaging video explanation by Elyse Cizek about how to spot AI-rendered interior design images. It’s also a concise, effective media literacy lesson.

“The choice is more educational and political than technological. What types of learning and education do we want for our children, our schools, and our society?” Mitch Resnick, founder of the Lifelong Kindergarten group at the MIT Media Lab (they developed Scratch), writes about his concerns and hopes when it comes to generative AI.

Leon Furze explains how schools misunderstand issues of teacher workload and offers practical ways generative AI can address the actual time challenges in a teacher’s day.

A comprehensive (and, thus, long) overview of the AI edtech market. The word “glut” comes to mind.

Even if you read everything Ethan Mollick writes, I recommend listening to this interview with Ezra Klein. Klein’s questions are thoughtful and practical, and Mollick remains the best AI explainer—of the technology, the potential, and the stakes—out there.

If you want to go deep on the the ethical and technical issues built into the models that train AI tools, spend some time with “Models All the Way Down,” a multimedia explanation of LAION-5B, one of the foundational datasets for generative AI.

I think you are absolutely correct to hypothesise that the future of education will be (even more than now) about the social element that a school or college can offer as a complement to the online AI-powered element of learning. The best educational experiences will make the most of social interaction both between teachers and students and between the students themselves.

Hi Eric - as always great thinking here and I love the shout out to Star Trek - Vulcan Learning. That said it seems it would be an extremely lonely way to learn. You couldn't be more quoting, "Matthew Rascoff of Stanford University has said, “School is learning embedded in a social experience.”

I would suggest two other elements of this AI in Education puzzle:

1. Maintaining common applications among teachers. We are currently struggling to find common ground for teachers. There are those who are the early adopters that are jumping at every new AI Tool for education they find and then those who are not reluctant but want proof of value added. Unfortunately what I see then is that students begin to get into the 'Teacher A says I can use this tool, and you (Teacher B) are saying I cannot.' This split is only growing as the firehouse of AI Tools is none stop

2. From a leadership perspective, the costs are going through the roof. Everything has moved to subscription base so we buy what we vet and think is going to genuinely be safe, valuable, and effective for students, but we have students who are buying their own tools and this creates the haves and have nots - what can we do about this?

Thanks again Eric for such great thinking and getting the conversations out there.

Chris Bell