What Schools Are Asking About AI

A snapshot from my travels, with questions and answers from me, from educators, and from students.

I’m writing to you from the middle of a burst of travel related to AI: facilitating professional learning workshops at schools and online, presenting at conferences, and meeting with teachers, administrators, and students. Inspired by a recent Ethan Mollick post, I thought I’d share some of the questions I’m being asked, the answers I’m giving and hearing from others, and some insights from the people who are wrestling with AI in school on a day-to-day basis. Questions are my favorite kind of data in my work: they reveal so much about how we think, feel, and wrestle with new ideas.

“If I’m going to encourage teachers to start experimenting with AI, what are some simple activities I should start with?”

I have a list of seven things to try in my first Substack post “Make Sense of AI.” I still think those ideas are useful entry points. What has become clear to me in the last three months is that educators should be doing this kind of practice together. When I facilitate hands-on AI activities with groups of educators, the deepest learning is done in comparing AI outputs, asking each other for help, and discussing how to expand on these introductory prompts. If you are a school leader with some power over teacher time, find an hour for your colleagues to sit at tables, open the chatbot of their choice, and try a variety of prompts.

“If I teach students younger than 13, how should I talk to them about AI?”

Most of the major chatbots have a minimum age requirement of 13 for use. This doesn’t mean, of course, that younger students aren’t using those tools. It also doesn’t mean we should avoid talking with younger students about AI: AI is a fundamental part of many of the online tools popular with young children like Roblox or YouTube Kids or Canva, to name just a few.

One of the best ideas I’ve heard was from an elementary school teacher who suggested a focus on “AI Readiness”: develop the skills young students will need to use generative AI ethically and effectively when they are able to do so on their own. Other elementary and lower middle teachers told me they are projecting an generative AI tool on a screen in their classroom and inputting student-suggested prompts themselves: for writing stories and poems, for creating and editing images, etc. The teachers use these collaborative activities to ask questions we should all be asking, no matter our age: Does this seem like a human made it? Where do you think AI got this information? How accurate is AI?

“How reasonable it is to think that A.I. could offer feedback on ideas or logic in analytical writing?”

It can already do this. I uploaded a pdf of my recent post “AI and the Question of Rigor” to Claude (the free level) and asked it a series of questions about my originality and logic. I found its answers compelling, especially on improving the logic of the argument. Here’s the whole exchange.

“Is AI going to change how we think about academic integrity?”

I appreciate how this question reframes the cheating question from being solely about student behavior to also being about school values and teaching practices. AI is changing how knowledge and skills are gained and applied in school and beyond. For example, consider this survey from the journal Nature asking post-doctoral researchers how AI is affecting their work.

Given that research professionals are using AI to do their work, how should we adapt how we teach students to conduct effective and ethical research? What would need to change in our current academic integrity policies to accommodate the way AI is changing the world we are preparing students to enter?

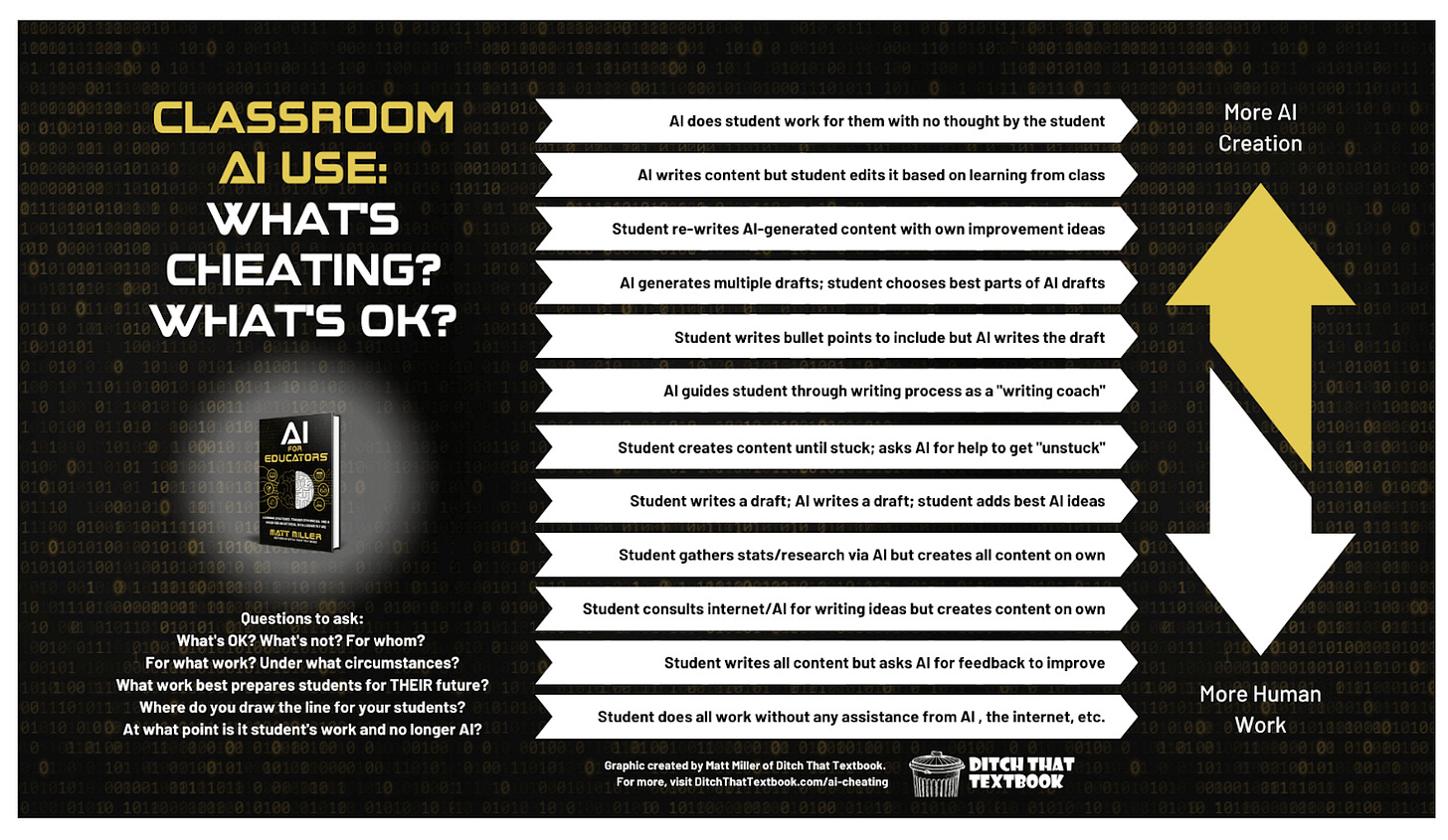

Schools have been debating and shifting the boundaries of appropriate academic assistance for decades, whether because of calculators or spell/grammar checks or tutors or the internet or other tools that make knowledge and support easier to access. Ditch that Textbook recently updated its “AI in the Classroom: What’s Cheating? What’s OK?” spectrum from seven elements to 12, a sign of how complex this conversation is getting.

In my experience meeting and listening to students, they are also wrestling with how to navigate the more nuanced areas between “I did this entirely myself” and “AI did this for me.” We should bring students into these conversations: they have valuable insights and experiences to share, and our decisions affect them the most.

“If we outsource giving feedback to AI, what obligations do we have to inform students and parents? Do we have an ethical obligation to add that it was generated by an AI application?”

As the above spectrum suggests, fully “outsourcing” any activity to AI and then presenting it as our own work is wrong. But, locating appropriate boundaries for assistance is not a students-only conversation. Educators often reuse or remix feedback from archival materials. They streamline the feedback process by creating guides and playbooks for students or using technology like text expanders to code templatized feedback. In what way is using AI to improve, create, edit, or streamline teacher work different? The same?

When I was at a conference in Atlanta a teacher shared an app he had built off of ChatGPT called LetterWise that writes college recommendation letters based on a few short prompts from a teacher. Should teachers use this tool? Should they disclose that their college recommendation letters are AI-assisted? What’s the value of an unassisted recommendation letter? For what it’s worth, when I later showed a group of students LetterWise, they loudly and with laughter declared that a teacher who uses it is “cheating.”

“What role do we as educators have in making students aware of how to use AI to improve or get proper assistance? Should we be leading lessons in class to facilitate student use and expose them to the possibilities?”

If I had to articulate one headline from my travels so far, it’s that schools’ stances towards AI are shifting from closed to open, but exploration of AI at schools remains fragmented and siloed. An “AI job to be done” in schools right now is building literacy across both staff and students. Here’s a simple single-point rubric I generated with Claude a few weeks ago. I think this is a great start for identifying the AI competencies both educators and students should develop.

Bringing in speakers and facilitators like me is a good first step, but literacy in any subject, including AI, is built through practice and reflection over time. Here are six suggestions for talking with students about AI.

“What other types of learning will we more heavily focus on as we learn to take advantage of these tools?”

I saw a presentation at the Innovative Learning Conference by two English teachers, Allen Frost and Claire Yeo, that made clear to me how important it is to be creative and student-centered about formative assessment in an age of AI. These teachers view formative assessment as a process through which students develop agency as thinkers and writers. Through visible thinking activities, discussion protocols, nontraditional writing prompts and formats, and learning portfolios, they ask students to bring their own identities and experiences into their work, documenting their process along the way. The work of English class becomes personal, meaningful, and communal. Formative assessment is not just about quizzing for knowledge: it is about empowering students to think for themselves and embrace the messy process of discovering the uniqueness of their ideas. Using AI to do their work for them not only becomes less effective, but less appealing. Use of AI, if used at all, becomes about exploring their own ideas and voices. Formative assessment might be where we and students find the most agency in our relationship with AI.

“What about encouraging students to use AI as they craft written work? How do you gather what students put in versus what AI spits out?”

I’ve been encouraged by the number of teachers who are moving this conversation out of the faculty room and into the classroom. I met teachers who began a unit or project by inputting the assignment into AI during class and having a discussion about the output: What do you like/not like about this output? Does it meet the parameters of the assignment? How can you do better than AI? One teacher imagined asking students to use a specific color in their writing for text generated or assisted by AI, then giving students extra time to go back and revise it into their own words. Another teacher simply asked students to follow MLA guidelines for citing AI.

There are technological options: tools like Khanmigo give teachers access to all interactions a student has with AI, and most of the major chatbots have features that allow for sharing of interactions via links. These transcripts could be teaching tools: a way to review AI conversations with students and discuss effective prompting and analysis of AI outputs.

“Can I train AI to teach like I do?”

A scenario an educator presented to me: If we trained AI on our assessment philosophies, examples of our feedback and assignments, writing samples, our resumes and bios, even audio recordings, could it become our teaching avatars, to review student work in our own voice and in our own style? It’s an interesting design challenge, and AI has already shown it learns quickly and can speak in the voice of others. Ethan Mollick’s excellent guide to two pathways to effective AI prompting offers a template for giving AI a detailed persona and voice. For me, it raises the question, If I can train AI to be any kind of teaching assistant I could imagine, what kind of teaching assistant would I want?

What Students Want to Know

I was so happy to speak at Phillips Academy Andover last month and find that half the audience was students. I want to end with some of the questions those students asked me. The conversations educators are having about assessment, academic integrity, and pedagogy are important, but these students are thinking about AI’s impact on their futures, on the world they are about to enter, and on issues of equity and justice. If we want to meet students where they are, this is where we need to go.

What are the most important questions and answers you’re hearing about AI?

Links!

Two helpful and engaging animations of how AI chatbots generate their responses, one from The Guardian and one from The Financial Times.

Vriti Saraf breaks down how well AI does at each level of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

I learned a lot from this profile of Rokhaya Diagne, a young entrepreneur in Senegal who is using AI to address health challenges in Africa and beyond.

EdWeek surveyed parents about AI in school. It’s a reminder that our learning about AI should be inclusive of families, who are interested but want to know more.

“Falsely accusing one student of cheating with AI is way worse than being tricked by all of them.”

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll share it with others. It’s free to subscribe to Learning on Purpose. If you have feedback or just want to connect, you can always reach me at eric@erichudson.co.

This is powerful to me for two reasons; your format works so well, answering real questions is definitely an exercise I want to do a version of!

Your advice re AI in education is fascinating and I'll share your newsletter with colleagues I have involved in education in our tiny nation.