AI Skills that Matter, Part 2: Lateral Reading

What does it actually mean to “critically evaluate” LLM output?

This is part two in a series about skills that both meet this AI moment and will outlast it. You can read part one, about extending the mind, here, and part three, about playfulness, here.

The disclaimers on generative AI tools are ubiquitous: “ChatGPT can make mistakes. Check important info.” “Gemini can make mistakes, so double-check it.” “Claude can make mistakes. Please double-check responses.”

It has been well-documented that large language models can get facts wrong, that they can fabricate sources, and that they can exhibit bias in a variety of ways. As a result, it’s hard to find a definition of “AI literacy” that doesn’t include some version of the phrase “learn how to critically evaluate AI output.”

But what does that actually look like? What is a relevant skill that we can learn and teach in order to critically evaluate the content generative AI creates?

For this post, I want to focus on lateral reading, a practice professional fact-checkers have used for years. I’m drawing from the excellent book Verified by information literacy experts Mike Caufield and Sam Wineburg. The book, which came out in 2023, is about the internet, not generative AI (although the authors include an afterword about ChatGPT, which debuted just as they turned the manuscript in to their publisher). I think its message has become only more important at this AI moment.

Caufield and Wineburg argue we must expand our definition of “critical thinking” to include online information literacy skills. Traditional critical thinking is about looking closely at a source, reading it deeply in order to analyze it. This works for analog material, but in an online world where information—good, bad, and ugly—is accessible, diverse, and growing exponentially, we must learn how to gather context, using “the web to check the web.”

Specifically, they identify three contexts to understand when looking at online information, contexts that the emergence of generative AI has made only more important.

“The context of the source. What’s the reputation of the source of information that you arrive at, whether through a social feed, a shared link, or a Google search result?

The context of the claim. What have others said about the claim? If it’s a story, what’s the larger story? If a statistic, what is the larger context?

The context of you. What is your level of expertise in the area? What is your interest in the claim? What makes such a claim or source compelling to you, and what could change that?”

Verified includes a number of practical, research-based strategies for assessing information online, but lateral reading is one that I think applies particularly well to generative AI.

The Context of the Source

What’s the reputation of the source of information that you arrive at, whether through a social feed, a shared link, or a Google search result?

Caufield and Wineburg write in their afterword about ChatGPT, “It’s easy to forget that [large language models] don’t know the subject—they just know the sort of things that people say about the subject, whether they’re true or not.”

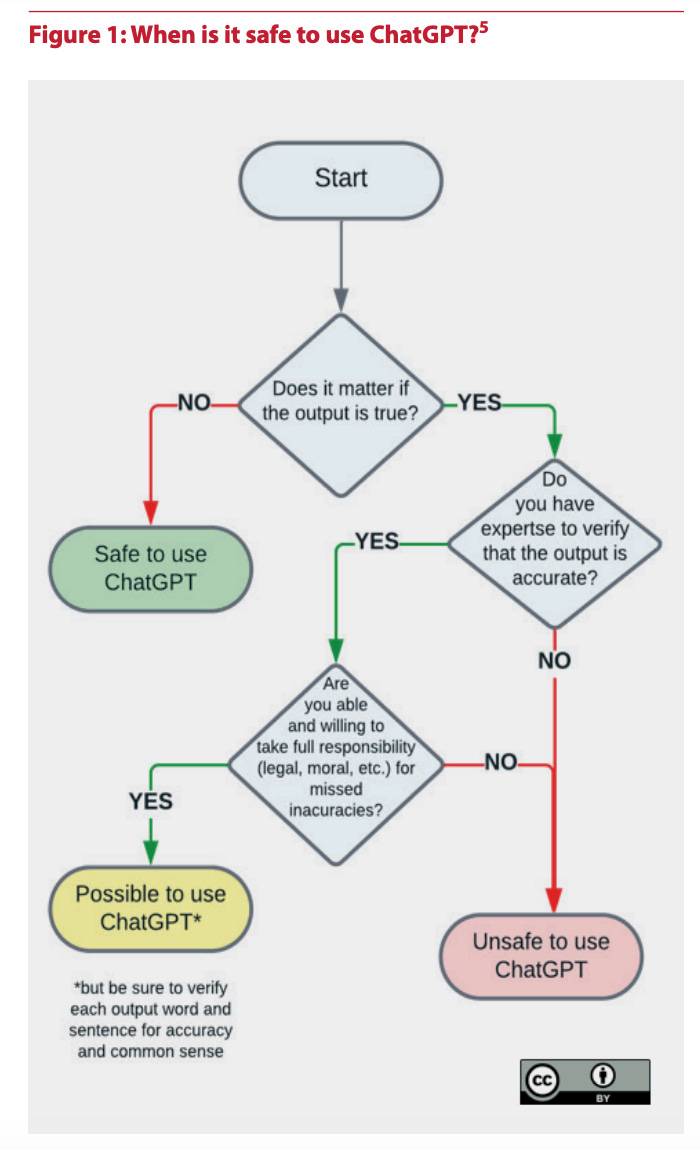

The best use of generative AI is not as a source of information, which is why AI experts have been telling us for over two years that we should be using the technology as an assistant, not an authority. If we are going to use generative AI to provide information, we must be prepared to verify the output. This 2023 graphic from UNESCO takes a strong stance.

My quibble with this graphic is that “expertise” is not just about what we already know, it’s about how we find things out. Prior knowledge might not be sufficient to evaluate AI output. Many, many people of all ages have been caught publishing and reproducing errors made by generative AI because they didn’t bother to verify the output against other sources, instead relying on their own intelligence and sense of what sounds plausible to them. This is a hazard of the way we have been taught to assess information, what Caufield and Wineburg call “vertical reading.” Vertical reading is traditional critical thinking, reading top to bottom, going deep instead of broad, trusting that we already know what we need to know. This doesn’t work for evaluating an online source.

Lateral reading is the process of gathering context by comparing one source and its claims against other sources. The first rule of lateral reading is to “get off the page,” to use search engines or other resources to find other resources and compare them to the original source. Fact-checkers read laterally by doing rapid-fire searches on many elements of a source, then skimming what they find to see how the original source rates in terms of its reliability and authority.

We should read laterally because an online source can easily appear reliable. The internet is awash in “cheap signals” like slick design, official-sounding titles, “research-based” claims, and “expert” testimonials. Cheap signals give a website a sheen of credibility that can mask poor or deceptive information.

Generative AI inundates us with cheap signals: quick responses, an authoritative tone, polished output, a user interface designed to give the appearance of “typing” and “thinking,” etc. The cheap signals in generative AI make us think the output is plausible when in reality the bot is trained to make it sound plausible. This doesn’t mean the output is always cheap; it means that part of using generative AI effectively is understanding what cheap signals are and that the best way to beat them is to look beyond them.

When we read laterally on the internet, we look at the name of the organization on a beautifully designed website and search for it to see who funds it or how often reputable sources refer to it. Or, we search the claims or positions of an organization’s whitepaper and see how other authoritative sources address the same topic or use the same content. Instead of scrolling up and down on a single page, we open new tabs and do new searches, learning about what Caufield and Wineburg call “the information neighborhood” in which our source resides.

Our approach to generative AI can be similar. For example, as I wrote recently, when I use generative AI for research and writing, I copy and paste AI-generated claims, quotations, and citations into Google, and in seconds I know if they are accurate or not. Or, I’ll paste output into AI research tools or databases to see if researchers have taken on the topic. Or, I’ll Google people named by chatbots to check their reputations. Each of these lateral reading moves takes just a minute, yet they reveal context and insight that simply reading the output would never provide. They help me make decisions about how to assess the output and what my next move should be.

The Context of the Claim

What have others said about the claim? If it’s a story, what’s the larger story? If a statistic, what is the larger context?

Caufield and Wineburg make clear that we still need to learn how to deeply analyze sources. Vertical reading and traditional critical thinking still matter. But, online, vertical reading is not only ineffective, but also time-consuming and intense. Lateral reading should be fast and lightweight, a matter of opening several other sources and skimming to see how much and by whom the topic has been covered in other places. I appreciated the analogy they make to cycling, where tactics that conserve energy (maintain aerodynamic lines) are often more effective than tactics that expend energy (pedal faster). Critical thinking online is about more than effort; it is also about strategy.

Here’s a quick example I did while crafting this post: I asked Claude a straightforward question, ”What were the causes of World War I?” I have superficial knowledge of the causes of World War I, and Claude’s initial response quickly went beyond it, referencing alliance systems and regional conflicts I wasn’t familiar with (or had forgotten in the two decades since I last studied World War I). I Googled a few of the names and terms and a quick scan of the results proved the same terms were repeated across a number of resources, including Wikipedia, museums, universities, and libraries.

Then, I asked Claude to provide me with a list of resources that would allow me to learn more. It gave me titles and a few links, all of which I searched and found to be real (a few of the links were broken, but the websites were legitimate). When I Googled the names of recommended resources, I found a few that were cited by universities and museums, so I bookmarked those and ignored the others.

In this process, I realized that I could use generative AI to help me read laterally. I asked Claude for search phrases that would help me verify its claims and that would offer diverse and/or challenging perspectives. It suggested a couple dozen, a few of which revealed new and useful information (“World War I historiography causes” and “July Crisis 1914 interpretations” were particularly helpful). Claude also suggested I search academic and library databases, not just the internet, a helpful reminder for students and educators who often have access to those databases.

Then, I copy and pasted Claude’s initial summary of the causes of World War I into ChatGPT and Gemini and asked for elaboration, for challenges, for new ideas, and for additional resources. The other bots added detail and reframed some ideas, but largely agreed with Claude. They had new sources to add, new search phrases I could use, and new ways to articulate the core ideas.

All of this took about 10 minutes, and by the time I was done I had several useful summaries and a list of legitimate resources to explore in more depth. To be clear, I’m not arguing that this is a perfect solution to assessing AI output, nor do I think we have to laterally read every interaction with a large language model. Instead, I want to show that skills like lateral reading ensure that we are in control when we use generative AI, and that they are not AI-specific. They are durable and transferable.

The Context of You

What is your level of expertise in the area? What is your interest in the claim? What makes such a claim or source compelling to you, and what could change that?

Part of learning how to read laterally is learning how to recognize and react to our own ignorance and biases. Self-awareness and decision-making are essential to effective use of any technology, especially generative AI. Helping students build information literacy skills aligns with a core function of school, which is teaching them how to be autonomous, ethical adults.

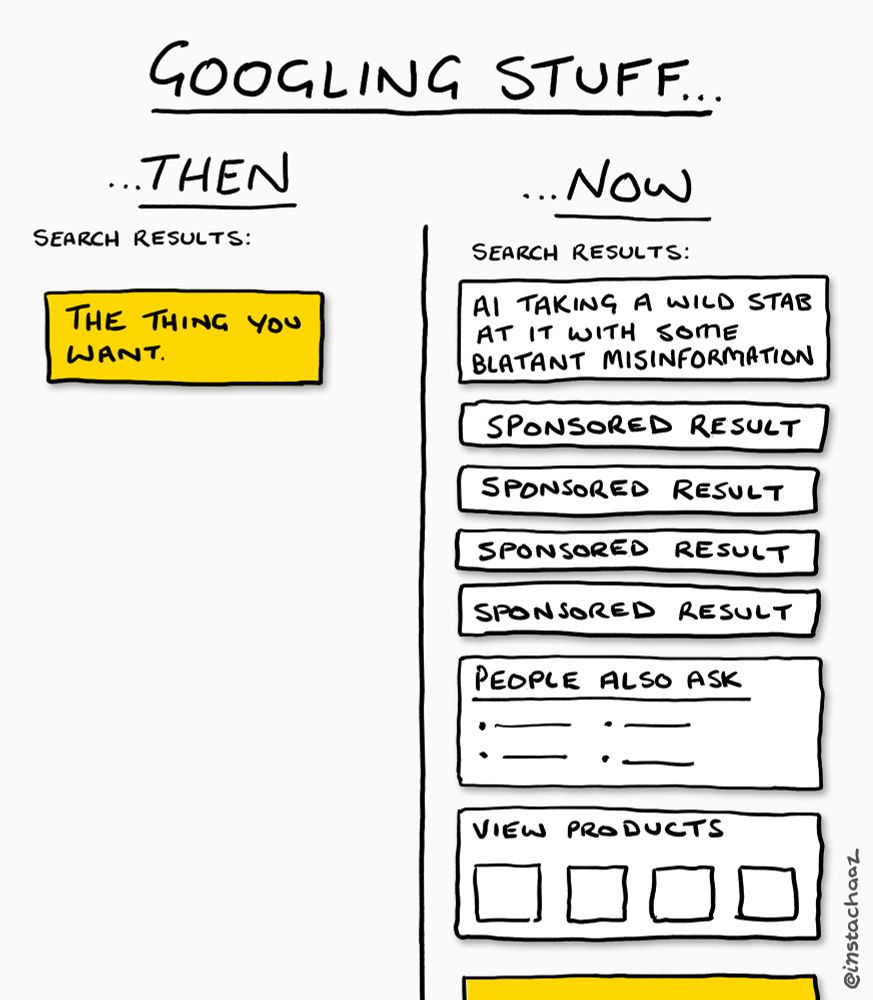

Generative AI has accelerated the trend of online information systems becoming byzantine and opaque, what Cory Doctorow famously called the “enshittification” of the internet. Take the basic Google search. As Chaz Hutton so crisply demonstrates in this visual, even this core function of the internet is now a minefield of unhelpful and distracting content.

Information literacy has never been more important, and it will only become more important as generative AI and a number of other factors make our online lives more complicated. Lateral reading is a teachable practice that helps our students—and us!—navigate the online world. More importantly, it can empower us to question it and contribute to its improvement. To embrace lateral reading and skills like it, however, we have to expand our notion of what it looks like to “think critically.”

Upcoming Ways to Connect with Me

Speaking, Facilitation, and Consultation

If you want to learn more about my work with schools and nonprofits, reach out for a conversation at eric@erichudson.co or take a look at my website. I’d love to hear about what you’re working on.

In-Person Events

February 24. I’ll be at the National Business Officers Association (NBOA) Annual Meeting in New York City. I’m co-facilitating a session with David Boxer and Stacie Muñoz, “Crafting Equitable AI Guidelines for Your School.”

February 27-28. I’m facilitating a Signature Experience at the National Association of Independent Schools (NAIS) Annual Conference in Nashville, TN, USA. My program is called “Four Priorities for Human-Centered AI in Schools.” This is a smaller, two-day program for those who want to dive more deeply into AI as part of the larger conference.

June 5. I’m a keynote speaker at the Ventures Conference at Mount Vernon School in Atlanta, GA, USA.

June 6. I’ll be delivering a keynote and facilitating two workshops (one on AI, one on student-centered assessment) at the STLinSTL conference at MICDS in St. Louis, MO, USA.

Online Workshops

January 9-March 31. I’m doing a four-part online series for school leaders, “Leading in an AI World.” We’ll cover AI literacy for leaders, crafting policy, and working with educators and families in managing change. This program is in partnership with the Northwest Association of Independent Schools (NWAIS), and is open to members and non-members.

January 23. I’m facilitating an online session with the California Teacher Development Collaborative (CATDC) called “AI and the Teaching of Writing.” We’ll explore the impact generative AI is having on writing instruction and assessment, and how to respond. Open to all educators, even if you don’t live or work in California.

Links!

Verified co-author Mike Caufield has a very good Substack of his own where he’s doing interesting experiments using generative AI to support critical reasoning.

A helpful interview with the learning scientist Bror Saxberg about why knowledge matters in the age of AI. I discovered Saxberg several years ago when I was doing a lot of work on competency/mastery learning. I recommend this 2017 interview with him, which still holds up and is worth comparing to the AI piece.

A story on the AI “cheating crisis,” told from the perspective of students who have been accused of using AI to cheat.

An overview of the data and research on the increasing importance of centering student agency in schools.

Your periodic reminder that ChatGPT is rapidly becoming the “Kleenex” or “Xerox” of generative AI, a brand name that transforms into a generic term. Here’s a great piece that explains why OpenAI wants that: “OpenAI is Visa.”

Take a look at Alberto Romero’s “You Must See How Far AI Video Has Come”

Hi, Eric, again we seem in lockstep. Check out this article I published just last week: https://nickpotkalitsky.substack.com/p/the-three-pathways-to-ai-source-literacy

I love the term lateral reading. I certainly hope media literacy has a renaissance in the era of the new AI.

I'm delighted to see you write about the idea of 'lateral thinking'. I've discovered the same process myself over this last year or so. It does take a bit more work but as you said, in addition to verifying what you're getting from an LLM, you are mind is often enlightened with another perspective or angle on the topic you're researching. You come away from the experiencing feeling more enriched with insight. And when the sources do not line up - you learn something extremely valuable - the art of discernment.

I'll be referencing this post to my list.