AI Skills that Matter, Part 4: Ethical Decision-Making

What is the job of schools in helping students become autonomous, ethical adults?

This is the fourth and final post in a series about skills that both meet this AI moment and will outlast it. Part one is about extending the mind. Part two is about lateral reading. Part three is about playfulness.

None of us should be making decisions about AI without understanding the ethics of those decisions.

Let’s define decision-making according to the CASEL framework: “The abilities to make caring and constructive choices about personal behavior and social interactions across diverse situations. This includes the capacities to consider ethical standards and safety concerns, and to evaluate the benefits and consequences of various actions for personal, social, and collective well-being.”

Decision-making is a teachable skill that is a key part of social-emotional learning (SEL), student agency, and adaptability in a rapidly changing world. Generative AI is an excellent case study in decision-making: it is relevant, technically and ethically complex, and disruptive, meaning the kinds of decisions we make about it are new and will keep changing.

Learning how to make ethical decisions about generative AI includes knowing when to and when not to use it, how AI works when you use it, what the tradeoffs of using it might be, and how use might affect yourself and others. So, what do we need to understand in order to make ethical decisions about generative AI?

AI’s Ethics and Biases

Because so many schools are focused on academic integrity, they tend to view AI ethics through the lens of “appropriate” or “inappropriate” use. But understanding AI ethics goes far beyond how we use it; it is understanding the ethics underpinning the design of the technology itself.

Large language models are trained by humans on human-created datasets, datasets composed of content that was generated primarily by Western, Anglo cultures like the U.S. Humans are biased, so we can expect LLM’s to replicate the biases that are embedded in these datasets and that are inherent to the people who decide how to train the models. Maha Bali has an excellent explanation of what these “cultural hallucinations” look like and how they should influence our use of AI.

Beyond AI’s biases, its troubling impacts on the environment, labor practices, intellectual property and data security issues, and other facets of society have been well-documented. This is especially true of the frontier models most of us use (GPT, Claude, Gemini, etc.), which are owned by large corporations seeking to rapidly scale them.

I meet many educators who have deep ethical concerns about generative AI. I encourage them to turn their concerns into curriculum. Teaching students about AI ethics is as important to AI literacy as teaching them about how to use generative AI and about how to evaluate its output. Knowing the human, environmental, and social impact of the technology should be a factor in deciding if and how to use it.

In terms of resources, you have a lot of options. Leon Furze’s “Teaching AI Ethics” series remains the most useful introduction I’ve come across. Explore existing AI ethics curriculum like CommonSense Media’s AI literacy lessons or MIT Media Lab’s curriculum for middle school students. Use activities like Ravit Dotan’s “anti-bias prompts” to test the bias of different bots for yourself or with students.

If I were designing an AI ethics curriculum, I’d be organizing it around these techno-skeptical questions based on Neil Postman’s work:

What does society give up for the benefit of this technology?

Who is harmed and who benefits from this technology?

What does the technology need?

What are the unintended or unexpected changes caused by the technology?

Why is it difficult to imagine our world without this technology?

We can’t make ethical decisions about AI without attempting to answer these questions.

Our Ethics and Biases

Ethical use of generative AI is not just about generative AI’s biases. It’s also about our own.

One of my favorite books on this topic is Design for Cognitive Bias by David Dylan Thomas. Thomas wrote the book for designers, but it’s full of insights about how our biases drive how we interact with the world, especially in how we make decisions, both consciously and unconsciously. Two of the dozens of biases Thomas covers in his book stood out to me when I was thinking about generative AI.

Cognitive fluency. Thomas explains, “We tend to translate cognitive ease into actual ease.” Examples of this bias abound: we look at how long a YouTube video is before we decide to watch it, the thickness of a book or the density of text on a page can affect our decision to read it, or the number of steps in a set of instructions can affect our decision to try something new.

The danger is that the desire for ease often trumps our critical thinking skills. “Easy to process,” Thomas writes, “becomes easy to believe.” He cites a number of studies: one shows that people with names that are easier to pronounce are promoted at work more often than those with names that are difficult to pronounce. Ease of name pronunciation also affects the popularity of stocks and mutual funds. Simply having a rhyme in a text makes it more appealing to people.

Generative AI is designed for cognitive fluency, to present information so efficiently and smoothly that we instinctively trust it. This is especially risky when AI output plays to our confirmation bias, our desire to believe things that confirm what we think we already know.

Anthropomorphizing technology. “Self-serving bias” is our tendency to take credit for success and blame others for failures. Thomas highlights an interesting mutation of this bias in our relationship with technology. While we are quick to blame technology for errors when we are new to the technology, the more we share personal information with it, the more we are more likely to trust it. We start giving technology credit for successes more than we blame it for errors, and we eventually start offering it “intimate self-disclosure” by sharing details of our lives in the way we might with a close friend. In other words, the more we share with technology, the closer we feel to it.

You need only watch this commercial for Gemini Live from Google to understand how well the companies who create these tools understand and leverage this bias.

In the absence of guardrails built into generative AI to interrupt cognitive fluency and mitigate anthropomorphizing, we have to make the conscious choice to slow ourselves down. Thomas cites Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman, which argues that cognitive errors are the result of thinking too fast. If we understand what our biases are and when they might affect our decision-making, we can slow ourselves down at key moments to think more carefully.

This requires teaching and learning. Practicing skills like lateral reading helps us to engage critically with AI output. Asking and answering questions like those in this AI Usage Self-Assessment tool that Amelia King at Dulwich College Shanghai created in Poe slows us down in productive ways. Thomas tells a story about sometimes processing problems in his rudimentary French: thinking through something in another language forces him to consider the issue more carefully. These are all examples of interrupting the biases that generative AI is designed to exploit, and therefore making better decisions.

The Relationship Between Autonomy and Decision-Making

I have written before about Rosetta Lee’s “Young Person’s Guide to Autonomy,” and I continue to believe it can be a useful tool for teaching students about AI decision-making.

Talking about using AI as a series of decisions rather than as “good” or “bad” behavior communicates to students that they have autonomy. As Lee shows above, autonomy is taking responsibility for making wise choices, not just deciding for the sake of deciding. That involves knowing when to reach out to others and seek advice.

Emphasizing decision-making with students is aligned to what we know about intrinsic motivation. As David Yeager writes in 10 to 25, conferring status and respect on young people by acknowledging their autonomy and teaching them about their autonomy will result in more responsibility and accountability, not less.

School as a Place for Ethical Decision-Making

In order for any of this to work, we have to change the culture of AI at our schools.

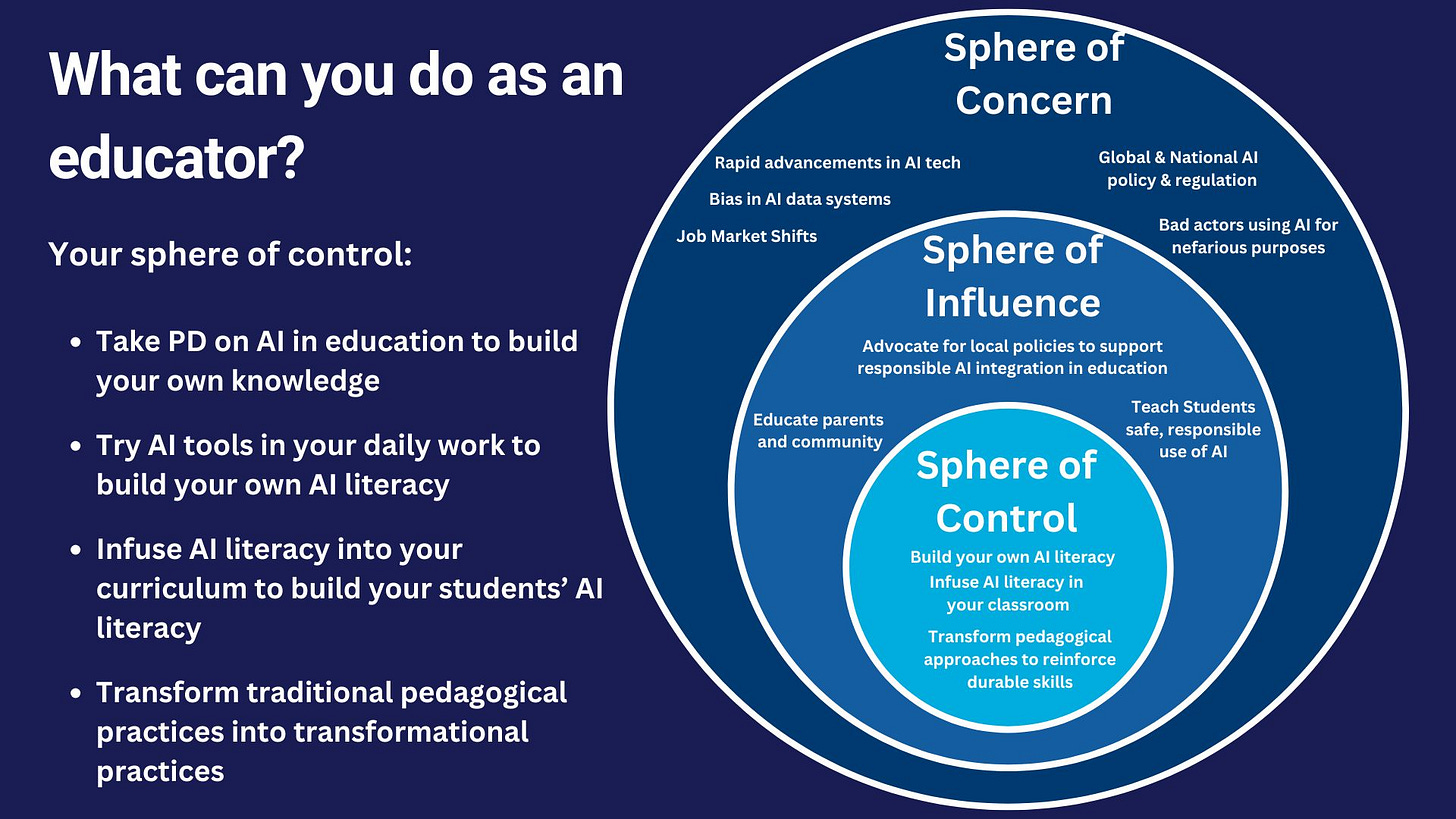

In my last post, I wrote about the importance of moving away from an AI culture of suspicion, secretiveness, and shame, and moving towards a more open culture that focuses on curious exploration of what it means to use AI ethically. As the below graphic from Vera Cubero shows, this is within our sphere of control when so many AI issues are outside of it.

Shifting the culture of a school on any topic requires the adults to ensure that the explicit and implicit cues in the day-to-day life of a school reflect the culture it seeks to create. This involves confronting some of our own cognitive biases.

How are you framing the AI issue? Thomas calls the framing effect “the most dangerous bias in the world.” The way we present information has a meaningful impact on people’s choices. I appreciated Thomas’ example of Philadelphia Police Commissioner Charles Ramsey’s reframing of the job of officers from “enforcing the law” to “protecting civil rights.” How we think about our job affects the decisions we make about the kind of work we do and how we do it.

How have you framed (explicitly or implicitly) the issue of generative AI since ChatGPT came out two years ago? As an academic integrity issue? An efficiency issue? What if we re-framed AI less as a technology and more as a current event? As a tool for exploring ethical decision making in general? How would reframing your school’s “AI job” change how you approach generative AI?

Which behaviors does your school culture incentivize? Thomas describes the “moral hazard of game play” as a mismatch between our stated goals and the behavior we actually incentivize. The classic example in education is grades: the goal of school is learning, but because we use grades to measure learning, the behavior we incentivize in students is getting good grades. The problem is that you can get good grades without learning (a problem that generative AI has only made worse). As Goodhart’s law states, as soon as a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.

Think about your current AI goals at your school. If the goal is “preventing cheating” or “restricting use,” how are you measuring success? What behaviors do those measures incentivize in both students and educators? Alternatively, if the goal became “developing ethical decision-making skills,” how would you measure success? What different behaviors might you incentivize?

How are we modeling ethical decision-making when it comes to AI? Is your school using AI-powered tools to monitor students’ online behavior? To enhance school security? To try to detect AI-generated content? All of these tools have the same ethical issues raised above, especially when it comes to bias and to risks to student privacy and data security. Using these tools without acknowledging and mitigating their ethical issues sends a clear signal to your community about how you make AI decisions.

A simple first step towards shifting AI culture is to follow Thomas’ advice, which is Nihil de nobis, sine nobis, “Nothing about us without us.” Think about who is most affected by your AI decisions and involve them in those decisions, whether that is students, teachers, families, groups who are particularly vulnerable to AI bias, etc. Be curious about their experiences, ask for their opinions, and apply their feedback. Show your community what ethical decision-making can look like.

Upcoming Ways to Connect with Me

Speaking, Facilitation, and Consultation

If you want to learn more about my work with schools and nonprofits, take a look at my website and reach out for a conversation. I’d love to hear about what you’re working on.

In-Person Events

March 1. I’m facilitating the third annual Teaching and Learning Conference at Buckingham Browne & Nichols School in Cambridge, MA, USA. Our focus is “Human-Centered AI in Education.” This is a free event open to all educators.

June 6. I’ll be delivering a keynote and facilitating two workshops (one on AI, one on student-centered assessment) at the STLinSTL conference at MICDS in St. Louis, MO, USA.

Links!

I’m enjoying Jane Rosenzweig’s new Substack, “The Important Work,” where classroom educators write about their experiences with AI. I particularly liked Warren Apel’s description of how the American School in Japan is using AI tools and “metacognitive checklists” to prioritize the process elements of writing. I also recommend history teacher Steve Fitzpatrick’s piece on how he created a custom GPT to engage students in a discussion about how AI can assist (or not) with reading challenging texts.

I have a lot of respect for Anna Mills, who wrote a thoughtful, honest post about how she has changed her mind about banning AI detectors in her class and started using them as one of many strategies in her teaching.

Mike Caufield is doing some of the most interesting work on using generative AI to support information literacy. Look at how he used ChatGPT to detect AI-generated images.

A long, technical, and informative attempt to answer the question, “How much energy does ChatGPT use?”

Flint AI has curated a collection of school AI policies.

Penn State has set up an “AI Cheat-a-thon.” It’s playful, literacy-forward, and focused on shared experiences between students and faculty.

I had a wonderful conversation with Amanda Bickerstaff and Mandy DePriest about human-centered AI for AI for Education’s February webinar. I also chatted with Seth Fleischauer about AI and student agency on the “Make It Mindful” podcast.

wow, this post is *packed* with good questions and provocative ideas. Thank you. I'm especially grateful for Neil Postman's list of questions, your suggestions for reframing the AI conversation, the AI use assessment tool, the autonomy resources... and the reminder about the Dan Jones (not Vera Cubero, right?) images on AI spheres of control, influence and concern. I'd seen it earlier but it was good to be reminded. I need to get the original link for that.

Oh and so grateful for your alt text - I took yours from the spheres of influence thing and used it in some upcoming slides - and attributed you, because wow, I took your alt text word for word :))

Just letting you know that we're reading this series in the little prompt writing class I'm teaching. We've finished the "how to" part of class and are moving into the experimental, project half. The next three weeks focus on value, ethics, and agency. So a million thanks for the perfect timing🙏🎉!!