Back to School With AI, Year Three

Let's try leading with questions we can explore ourselves, not with someone else's answers

Learning on Purpose turns two next week!

In August 2023 I launched this Substack with a “Back to School with AI” series, five posts with five human-centered ways to approach AI at school. Feeling nostalgic, I re-read them last week. So many of the tips and details seem quaint (a lot has changed!), but I still stand by that series as a process we can follow to move forward on AI, not just wrestle with it or debate it or react to its constant changes.

So, as we enter another back-to-school season here in the U.S., I offer a kind of update on that series. I don’t have a to-do list for you; I just have questions that I’d like individual educators and schools to answer. We have to let go of the idea that there’s a “right” way to “do AI.” Instead, we have to begin to find our own answers to the important, deep questions that AI raises about education, answers that suit who we are and who our students are.

“Make Sense of AI” (original post)

The three questions that shaped my very first post still shape my work, and I think they are good questions to help schools focus in the noisy world of generative AI in education:

What is our job as educators in a world being disrupted by AI?

How might AI help students think more deeply?

How might AI help educators become better designers and facilitators of learning experiences?

You could lose days reading other people’s takes on these questions, but the AI hill I will die on is that the best way to make sense of AI is to use it. Regardless of your personal opinion, regardless of how much you want or intend use AI in the long term, every educator should be developing hands-on knowledge and skills about how well generative AI tools work for tasks relevant to them, then considering what role it can and should play in their classrooms and schools. You will be a better AI advocate, a better AI resistor, or simply a more AI-aware educator if you use these tools for yourself.

When I started Learning on Purpose, most teachers were new to generative AI. Two years later, the spectrum of educator knowledge and skills is wide: in any single professional development workshop, I will meet at least one educator who is fluent in some of the most innovative uses and at least one educator who has never opened a chatbot. No matter where you are on this spectrum, however, I’m going to offer a reflection protocol I learned from students and educators at Urban Assembly Maker Academy a few years ago:

What do I know? What do I need to know? What are my next steps?

Try answering the above questions for yourself and set some meaningful, do-able next steps to deepen your AI knowledge and skills. I created a playlist of resources and ideas for educators a couple of months ago that’s a good place to start digging in.

“Talk With Students About AI” (original post)

I still have the same question that led me to write the original post, Why don’t we talk more with students about important issues in education? After two years of AI immersion, 1) I know we are still not talking to students about generative AI in an open, generative way and 2) this has increased my sense of urgency about changing this dynamic.

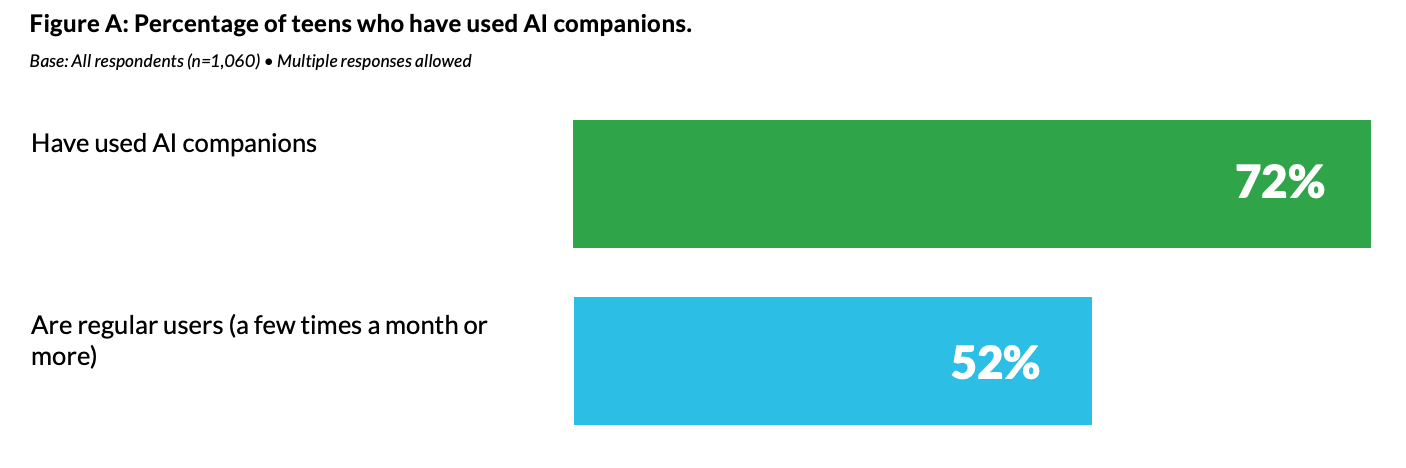

Many educators tell me they are reluctant to engage their students on the topic of generative AI until they are “better at it” or “know a lot more.” While schools wait for adults to be ready to talk to students about AI, students are adopting the technology at a rapid pace, using it in increasingly diverse ways, and doing so without a lot of guidance or interventions from adults. This use extends far beyond school work, from engaging with companion bots to using AI as a form of play.

Importantly, these surveys show over and over that students want to talk to adults about AI. The traditional dynamic of the classroom relationship, where the teacher is the expert and the student is the novice, simply does not apply here. All of us are bombarded by new updates and rapid advancements in generative AI. All of us are developing knowledge and skills at different paces. We should talk. We should compare notes. We should decide together what might be next. Offering curiosity and collaboration to students is more important than delivering instruction or tools.

Here are the questions I ask students, and I offer them here as an entry point for you to begin your own conversations:

Do you use generative AI tools? If so, what does that use look like (how often, which tools, which uses)? If not, why not?

What do you think of these tools? In what ways are they (not) helpful?

What excites you about AI? What do you hope it will be able to do for you and for others?

What worries you about these tools? What gives you pause?

How would you describe the way AI is approached at your school (implicitly and explicitly)? What would you want adults to know and do about AI at your school?

“AI and Competency-Based Education” (original post) and “AI and the Question of Rigor” (original post)

Once you’ve made some sense of AI and once you’ve talked with students about AI, I think you’re ready to consider the impact AI is and will have on learning and assessment, which is what these two posts were about. This is the most differentiated area of AI in education: a lot depends on discipline, grade level, learning goals, and student and teacher confidence and competency.

What are our learning goals for students in the classroom and beyond? How have they been articulated, published, and taught? When we look at our goals in the context of generative AI, what do we need to stop, start, and continue doing?

Are we concerned about the integrity of our assessments or are we concerned about how students go about learning? Those are two different questions that require different responses.

On learning: If students are using AI to learn and are still performing well on assessments, what exactly are our concerns? What do we and students need to know about AI as a tool for learning?

On assessment integrity: What can we not measure through in-class, supervised assessments? What is out-of-class work that remains important to us? What needs to be revised or transformed about those assessments to address our concerns about their validity?

Which assessments have proven to be fairly resistant to unethical use or overuse of generative AI? How do we know? Some of those assessments will obviously be supervised, in-class assessments, but what about the others? What are the design elements of those assessments that seem to fight the urge to delegate to AI? How can those elements be integrated into other assessments?

Who in your school is revising or transforming assessments to integrate generative AI? Why did they make that change? What impact have these changes had on the students and the teacher? What are the design elements of those assessments that elevate productive use of the technology? How can those elements be integrated into other assessments?

“Making Decisions about AI” (original post)

I structured this post around polarity mapping, a system for visualizing the elements and tradeoffs of complex decisions. I still believe that AI offers more polarities to be managed than problems to be solved, but, years into the emergence of generative AI in education, there are certain areas where decisions need to be made so that school communities can move forward. School leadership teams need to make some choices and communicate them with care and intention.

I would ask school leaders to answer these questions:

What does your school believe about the role of generative AI at school? What do you see as your school’s responsibility in an AI age?

What are the non-negotiables of approaching AI at your school? For example, can one academic department institute an AI ban while others endorse its use? Can one teacher? Can teachers use AI detectors to scan student work? If so, which ones? If not, what should they do if they are concerned about student AI use?

What framework have you offered students and employees about how to decide if and how to use generative AI in their work? How will you teach them how to use that framework?

AI is a Culture Issue, not a Technology Issue

In looking back on the Learning on Purpose archive, I have written about exactly one non-AI topic: trust, both what it is and how we build it and break it. Conveniently, this is also the topic I think is lurking underneath so many of our AI challenges.

I’m not talking about trust in AI or the companies who own the frontier models. That trust has not yet been fully earned. I’m talking about trusting each other. Trust can be a human-centered strategy to address a technology that is powerful, flexible, and almost impossible to monitor and detect.

Is trust an intentional and visible part of your school culture? If not, why not? Can you trust your students and your colleagues to make good decisions about generative AI? If so, what can you do to ensure that trust is not broken? If not, what is required to build it?

Upcoming Ways to Connect With Me

Speaking, Facilitation, and Consultation

If you want to learn more about my work with schools and nonprofits, take a look at my website and reach out for a conversation. I’d love to hear about what you’re working on.

Online Workshops

September 24. I’ll be facilitating “Making Sense of AI,” a workshop for educators on generative AI that introduces the knowledge and skills required to address AI at school and in the classroom. Offered in partnership with the California Teacher Development Collaborative (CATDC). Open to all, whether or not you live/work in California.

October 15. I’ve partnered with CATDC on a new offering, “Practical AI for School Leaders,” a hands-on workshop that focuses on the uses and tools of AI relevant to the day-to-day work of school administrators in academic and non-academic roles.

October 16-17. I’ll be facilitating a two-part series for school leaders on developing AI position statements and ethical guidelines. Offered as part of the National Association of Independent Schools (NAIS) Strategy Lab series.

Links!

Developments in AI in education to pay attention to: Instructure (Canvas) has partnered with OpenAI (ChatGPT) and Google has loosened age restrictions and made a number of other AI-related updates for education users and ChatGPT has a “study mode” (read Claire Zau’s review) and NotebookLM has video overviews and Perplexity has a new browser called Comet which can perform web-based.

While we’re on latest developments, watch David Wiley use ChatGPT’s new agent to complete online assignments, then watch George Veletsianos use the same tool to grade student work.

Emily Pitts Donahoe with a detailed overview of how she’s going to approach AI with her students this fall.

You should read Phillipa Hardman’s summary of 18 studies of generative AI’s impact on instructional design. As a little experiment, plug in the word “teaching” every time she uses “instructional design.”

Leon Furze looks at several “AI Resistance” letters circulating in education spaces and offers a nuanced take on how to think about educators’ refusal to engage. The point on which I most agree: the binary “you are either for AI or against AI” discourse is exhausting and unhelpful.

“Assessments aren’t something students do for fun. Assessments are something students do because we require them to. Because we need them to…And since students do assessments for us, so that we can do the jobs we get paid to do (e.g., submitting grades at the end of the term), it seems reasonable that we would take on the responsibility of finding a pathway forward.” David Wiley on having a more productive conversation about AI and assessment.

What if the biggest threat of AI in the classroom is not to our curricula and assessments but to the relationships students have with us and with their peers?

I had a great conversation with Peter Horn about human-centered AI on the Point of Learning podcast.